Arbitral Award Need Not Be Set Aside Merely For Being Inadequately Reasoned; Courts Can Explain It: Supreme Court

|

|The Supreme Court observed that where an arbitral award, which exhibits no perversity, contains reasons but appear to be insufficient or inadequate, the Courts need not set it aside while exercising its powers under Section 34 or Section 37 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (‘Act of 1996’).

The Court dealing with the challenge against such awards should explain such underlying reasons for a better and clearer understanding, it added.

The Court added that while doing so, they must differentiate between an arbitral award where reasons are either lacking/unintelligible or perverse and an arbitral award where reasons are there but appear inadequate.

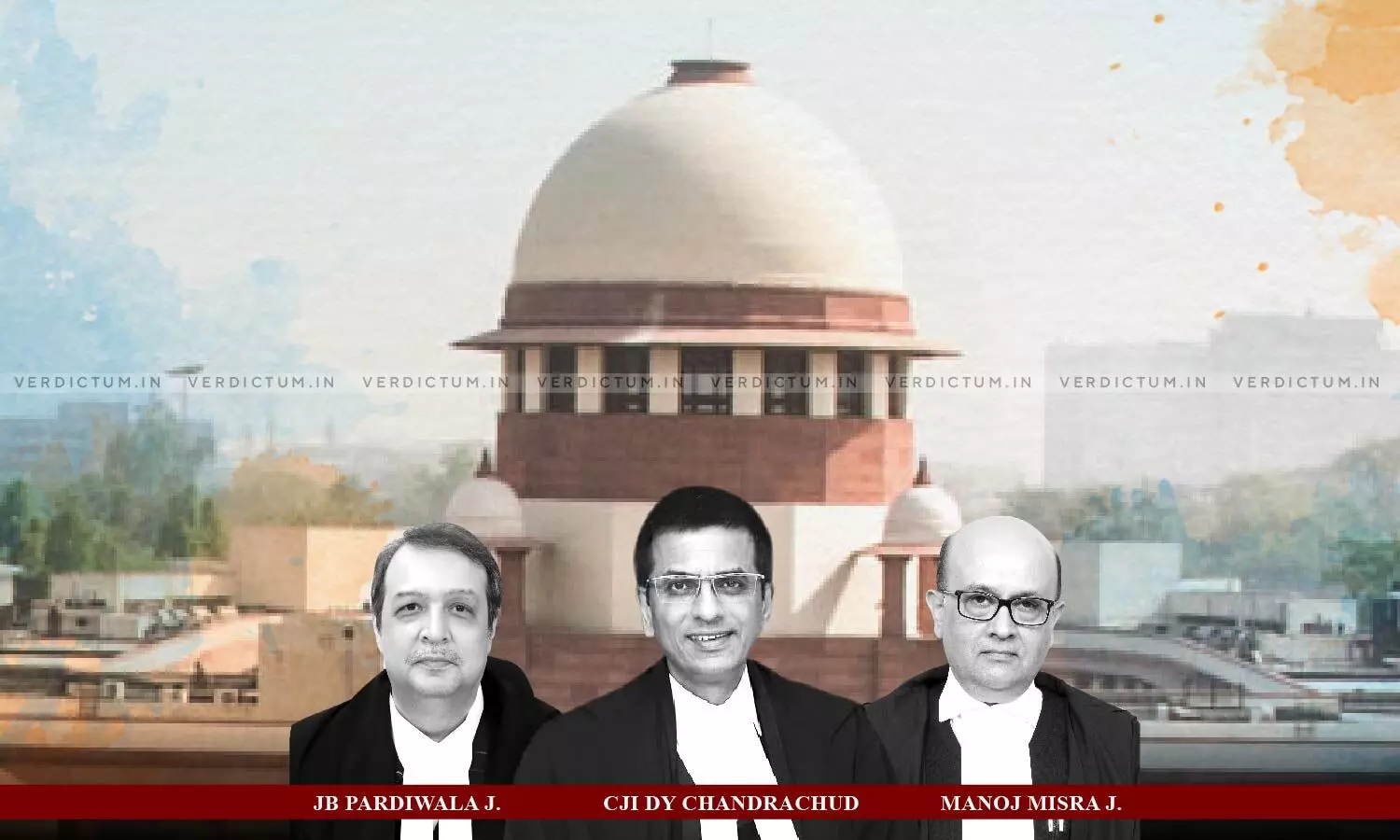

The Bench of Chief Justice DY Chandrachud, Justice JB Pardiwala and Justice Manoj Misra held, “In our view, a distinction would have to be drawn between an arbitral award where reasons are either lacking/unintelligible or perverse and an arbitral award where reasons are there but appear inadequate or insufficient. In a case where reasons appear insufficient or inadequate, if, on a careful reading of the entire award, coupled with documents recited/ relied therein, the underlying reason, factual or legal, that forms the basis of the award is discernible/ intelligible, and the same exhibits no perversity, the Court need not set aside the award while exercising powers under Section 34 or Section 37 of the 1996 Act, rather it may explain the existence of that underlying reason while dealing with a challenge laid to the award. In doing so, the Court does not supplant the reasons of the arbitral tribunal but only explains it for a better and clearer understanding of the award.”

Advocate Abhimanyu Bhandari appeared for the Appellant, whereas Senior Advocate Gaurab Banerjee appeared for the Respondents.

Appeals were filed assailing a judgment passed by the Madras High Court, which, by exercising powers under Section 37 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996, read with Section 13(1) of the Commercial Courts Act, 2015 and Clause 15 of Amended Letters Patent, 1865 read with Order XXXVI Rule 9 of O.S. Rules, the High Court allowed the appeals, set aside the judgment and order of the Single Judge and restored the arbitral award.

The Appellant, i.e. OPG Power Generation Private Ltd (‘Appellant’), which is a subsidiary of Respondent No. 2, floated a composite tender for the design, manufacture, supply, erection and commissioning of air-cooled condenser unit (ACC Unit) for a Thermal Power Plant (Project) at Gummidipoondi in the State of Tamil Nadu. The commission took place in May 2015, thereafter, Enexio Power Cooling Solutions, i.e. Respondent No. 1(‘Enexio’), billed an amount of Rs. 46,71,04,493 but the amount paid to it was Rs. 39,59,19,629 only. This gave rise to the arbitral dispute. According to Enexio, Rs.6,75,15,631 remained payable to it. Whereas, according to the Appellant, nothing was due from the remaining amount.

The matter went for arbitration, and an award was passed saying Gita Power, being the holding company of Appellant, had actively participated in the negotiations and had placed the purchase orders; therefore, both Gita Power and Appellant were jointly and severally liable. Secondly, the award also said that the Respondents were entitled to the unpaid principal amount with interest. Thirdly, the tribunal held that declaratory relief sought by Enexio qua the debit notes (i.e., towards liquidated damages and customs duty) was beyond the period of limitation prescribed by Article 58 of the Limitation Act, 1963.

The core issues, inter alia, raised by the Court were whether the arbitral award is in conflict with the public policy of India or/ and is vitiated by patent illegality appearing on the face of the award; whether Gita Power could have been subjected to arbitration and made jointly and severally liable along with Appellant for the award, when the project beneficiary was Appellant and whether Enexio’s claim for the outstanding principal amount is barred by limitation.

Legality of Arbitral Award

The appellant had argued before the Court that the Tribunal had adopted a different yardstick for adjudicating the claim than what was adopted for the counterclaim. This argument was rejected by the Court after reading the award in its entirety. It added that the Tribunal did not reject the counterclaims qua liquidated damages and custom duties as barred by limitation, rather, it rejected them on merit.

“Liquidated damages were denied because Enexio was entitled to 539 days extension for completion; and customs duties were found payable by the purchaser. The findings thereon are based on construction of the terms of the contract with reference to the conduct of the parties, therefore, it does not call for interference under Section 34 of the 1996 Act… Even otherwise, the mistake, if any, committed by the arbitral tribunal in using the words ‘ongoing negotiations’ in place of acknowledgement is trivial does not go to the root of the matter as to have a material bearing on the conclusion. Therefore, for this mistake alone, the award is not liable to be set aside.”, the Court said.

Joint & Severally Liable

As regards the issue of whether Gita Power and Appellant were jointly and severally liable for the award, the Court, while relying on its judgment in Cox & Kings Ltd. v. SAP India (P) Ltd. (2024), said that the “Group of Companies Doctrine” would apply on Gita Power and would bind it with the arbitration agreement and fasten it with liability, jointly and severally with Appellant.

Limitation

For the issue of limitation, the Court considered the timeline of the events and relied on the provisions of the Limitation Act, 1963, such as Article 14 of the Schedule to the 1963 Act, which is pari materiaArticle 52 of the First Schedule to the Limitation Act, 1908 and Article 55 and Section 73 of the Indian Contract Act. Whereas Article 18 of the Schedule, which is pari materia Article 56 of the First Schedule of the 1908 Act, applies where: (a) the suit/claim is for the price of work done by the plaintiff/ claimant for the defendant at his request, and (b) no time has been fixed for payment.

Thus, the Court said where a suit is for goods supplied and work done by the contractor, the price of materials and the price of work are separately mentioned, and the time for payment is not fixed by the contract, Article 14 will apply to the former claim, and Article 18 to the latter. But where a claim is made for a specific sum of money as one indivisible claim on the contract, without mentioning any specific sum as being the price of goods or price of the work done, neither Article 14 nor Article 18 will apply, but only Article 55, which provides for all actions ex contractu (i.e., based on a contract) not otherwise provided for, would apply, it said.

“Thus, failure of a party to a contract in performing its obligation(s) thereunder could be considered a breach of contract for the purpose of bringing an action against it by the other party. In such an event, the other party can claim compensation or damages, or/ and, in certain cases, obtain specific performance.”, the Court held.

The Court also highlighted that in the present case, the limitation period started to run from March 19, 2016, and within three years therefrom, in the minutes of the meeting dated April 19, 2018, there was a clear acknowledgement that the amount claimed by Enexio was the balance amount payable.

It held that such an acknowledgement was sufficient to extend the limitation period as it admits the existing liability of the appellant(s) qua the balance amount payable to the claimant under the contract, and the benefit of such an acknowledgement would not be lost merely because a set-off is claimed, inasmuch as clause (a) of the Explanation to Section 18, inter alia, provides that an acknowledgement for the purposes of this Section may be sufficient though it is accompanied by a refusal to pay, or is coupled with a claim to set off.

Counter Claim

The Court also considered the issue of whether the counterclaim of the Appellant was barred by limitation. The Court relied on the provisions in Section 23(2A) and Section 43(1) of the Act of 1996 and Section 3(2)(b) of the Limitation Act 1963. It said that it is well settled that a counterclaim is like a cross suit or a separate suit, and the limitation of a counterclaim is to be counted from the date of accrual of the cause of action which it seeks to espouse, thereof, it is quite possible that even though a suit or a claim is within the period of limitation, the counterclaim may well be barred by limitation if the cause of action espoused therein accrued beyond the prescribed period of limitation.

The Court observed, “Where the respondent against whom a claim is made, had also made a claim against the claimant and sought arbitration by serving a notice to the claimant but subsequently raises that claim as a counterclaim in the arbitration proceedings initiated by the claimant, instead of filing a separate application under Section 11 of the 1996 Act, the limitation for such counterclaim should be computed, as on the date of service of notice of such claim on the claimant and not on the date of filing of the counterclaim.”

The Court highlighted that the arbitral tribunal, in its award, had failed to state that it was treating the minutes of the meeting as an acknowledgement within the meaning of Section 18 of the 1963 Act. The Court concluded that the omission was trivial and did not travel to the root of the award; therefore, the appellate court was well within its jurisdiction to explain the underlying legal principle which the arbitral tribunal had applied, and in doing so, it did not supplant the reasons provided in the award.

Accordingly, the Court upheld the decision of the Division Bench, which restored the arbitral award and thereby dismissed the appeals.

The Court, inter alia, summarised: 1) the tribunal was justified in holding that Gita Power was bound by the arbitration agreement and jointly and severally liable along with Appellant to pay the awarded amount; 2) limitation for the claim was governed by Article 55, and not by Articles 14, 18 and 113, of the Schedule to the 1963 Act and 3) limitation for the claim and counterclaim on the basis of acknowledgement was rightly considered.

Cause Title: OPG Power Generation Private Limited v. Enexio Power Cooling Solutions India Private Limited & Anr. (Neutral Citation: 2024 INSC 711)

Appearances:

Appellant: Advocate Abhimanyu Bhandari and AOR Aman Gupta

Respondents: Senior Advocate Gaurab Banerjee, AOR Sarvesh Singh Baghel, Advocates Mayank Mishra, Ayshwarya Chandar, Aishwarya Chandar and Anukriti Kudesia.