'Recommendatory Guidelines Under The Garb Of Mandatory Rules': SC Directs Govt. To Prescribe Mandatory Accessibility Standards To Implement Rights Of Persons With Disabilities Act

|

|The Supreme Court has held a rule in the Rights of Persons with Disabilities Rules, 2017 prescribing standards for accessibility for persons with disabilities to be ultra vires of the RPwD Act concluding that several of its provisions appear to be recommendatory guidelines under the garb of mandatory rules. This, the Court said, is contrary to the legislative intent of the Act which creates a mechanism for mandatory compliance.

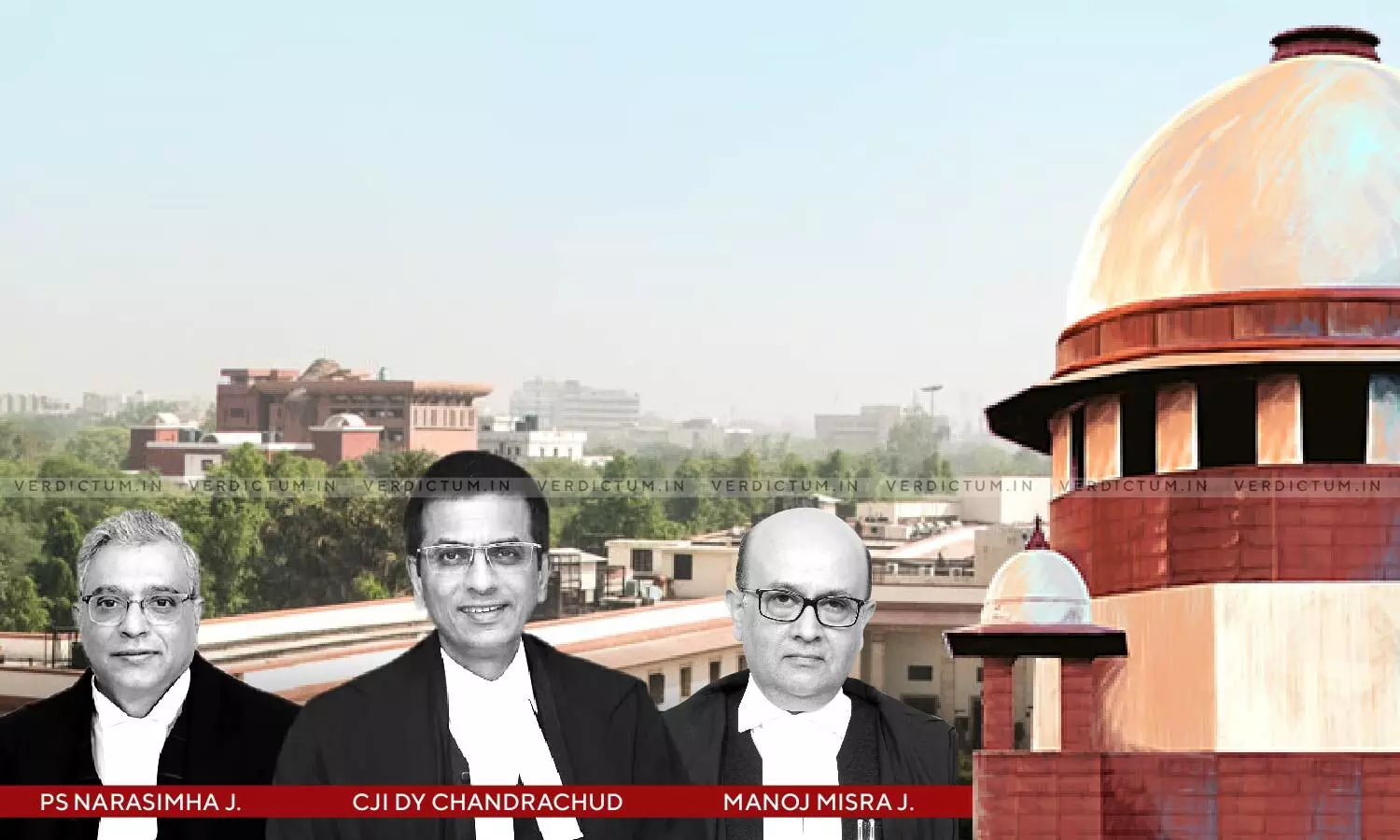

A three-judge Bench comprising the Chief Justice of India Dr. D.Y. Chandrachud, Justice J.B. Pardiwala and Justice Manoj Misra held,"Rule 15, in its current form, does not provide for non-negotiable compulsory standards, but only persuasive guidelines. While the intention of the RPwD Act to use compulsion is clear, the RPwD Rules have transformed into self- regulation by way of delegated legislation. The absence of compulsion in the Rules is contrary to the intent of the RPwD Act."

The Court directed the Union Government to delineate mandatory "non-negotiable" rules to ensure accessibility for persons with disabilities. After the formulation of mandatory rules, the Union Government, States and Union Territories must ensure that the consequences for non-compliance as prescribed in the RPwD Act, such as holding back of completion certificates for buildings are implemented.

Case Background

The Judgment arose from a Writ Petition filed in 2005 by one Rajive Raturi, a visually challenged person who works with a human rights organisation. The petition sought directions to the to take certain measures towards ensuring safety and accessibility in public spaces, such as roads, public transport and other facilities for visually challenged persons.

The Court passed a Judgment in December 2017 identifying eleven action points pursuant to the RPwD Act and the Accessible India Campaign for compliance. The Union Government, States and Union Territories were directed to file their compliance affidavits, but most of the States and Union Territories. Most only filed their affidavits after being reminded by the Court, and some did not file it in the stipulated format. On 29 November 2023, the Court noted that several Orders had already been passed regarding the poor progress made by the Union, States and Union Territories in implementing the provisions of the RPwD Act. The Court was of the view that a comprehensive exercise was necessary to assess the situation on the ground.

The Court directed the Centre for Disability Studies (CDS) at National Academy of Legal Studies and Research (NALSAR) to submit a report on the steps required to be taken in accordance with the guidelines and the Accessible India Campaign to, make all government buildings, airports, railway stations, public transport carriers, all Government websites, all public documents and the Information and Communication Technology ecosystem fully accessible to PWDs. The NALSAR-CDS was directed to file a report within six months.

Pursuant to the directions, a report titled 'Finding Sizes for All: A Report on the Status of the Right to Accessibility in India' was filed after conducting surveys, expert interviews and recording first-person accounts documenting accessibility barriers across various spheres.

Reasonable accommodation and a two-pronged approach to accessibility

Accessibility is not merely a convenience, but a fundamental requirement for enabling individuals, particularly those with disabilities, to exercise their rights fully and equally, the Court said. "Without accessibility, individuals are effectively excluded from many aspects of society, whether that be education, employment, healthcare, or participation in cultural and civic activities. Accessibility ensures that persons with disabilities are not marginalised but are instead able to enjoy the same opportunities as everyone else, making it an integral part of ensuring equality, freedom, and human dignity. By embedding accessibility as a human right within existing legal frameworks, it becomes clear that it is an essential prerequisite for the exercise of other rights."

The Judgment notes that addressing accessibility requires a balanced approach that focuses on both adapting existing environments and proactively designing new spaces with accessibility in mind. "A two-pronged approach is needed - one that focuses on ensuring accessibility in existing institutions and activities and the other that focuses on transforming new infrastructure and future initiatives. Both are essential to achieving true inclusivity in society."

According to the Court, it is crucial to understand the relationship between reasonable accommodation and accessibility, as both are essential for achieving equality for PWDs. While accessibility generally refers to the removal of barriers in the environment or infrastructure to ensure equal access for all, reasonable accommodation is more individualised. Explaining reasonable accommodation, the Court said, "It involves making specific adjustments to meet the unique needs of a person with a disability. In other words, accessibility ensures that environments are designed to be inclusive from the outset, while reasonable accommodation ensures that individuals who face specific challenges can enjoy their rights on an equal basis in particular contexts."

The Court found it crucial to reiterate that accessibility is an "ex-ante duty," meaning that the State is required to implement accessibility measures proactively, before an individual even requests to enter or use a place or service. This proactive responsibility, it said, ensures that accessibility is embedded in the infrastructure and services from the outset. "The State must establish broad, standardised accessibility standards in consultation with disability organizations, ensuring that these standards are enforced by service providers, builders, and all relevant stakeholders. The state cannot negate its duty to accessibility by relying solely on existing standards or waiting for individual requests."

In Vikash Kumar v. Union Public Service Commission (2021) the Court had highlighted that reasonable accommodation must consider not only the benefit to the individual but also to others in similar situations in the future. Accessibility and reasonable accommodation require "a departure from the status quo" and challenges in implementing such measures should not be seen as barriers to inclusion, the Court had held, adding that complications in implementation are inevitable, but they should not be used as an excuse to deny accommodations.

Inconsistencies in the Existing Legal Framework

The NALSAR-CDS reported that there is an inconsistency in the legal framework, which lies at the root of the slow progress. The Court noted that the marginal note to Rule 15(1) states that it contains 'Rules for Accessibility' and uses “shall” in its chapeau indicating that the standards that follow in clauses (a) to (p) are mandatory.

However, it noted, "a perusal of the 'standards' for accessibility laid down in clauses (a) to (p) of Rule 15(1), in the form of the guidelines issued by the concerned ministries, indicates that most of these documents do not contain mandatory or non-negotiable prescriptions. The use of the term ‘guidelines’ rather than ‘rules’ in most of these documents is not a mere difference in nomenclature, but is evident in the content of these documents as well."

As an example, the Court cited a document titled 'Harmonized Guidelines & Standards for Universal Accessibility in India 2021' by the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs and observed that the idea of the document is not to lay down rules, which are non-negotiable and have tangible consequences in case of non-compliance, but rather to merely “sensitize”, “recommend” and “guide”. It was also noted based on the NALSAR-CDS report that several of these guidelines contain different standards for the same or similar accessibility requirements and allegedly contain technical errors. In such situation, the Court said, it is difficult to fathom which of the requirements is “mandatory” to follow.

"While Rule 15 creates an aspirational ceiling, through the guidelines prescribed by it, it is unable to perform the function entrusted to it by the RPWD Act, i.e., to create a non- negotiable floor. A ceiling without a floor is hardly a sturdy structure." the Court observed.

Conceding that accessibility is a right that requires 'progressive realization', the Court said this cannot mean that there is no base level of non-negotiable rules that must be adhered to. "While the formulation of detailed guidelines by the various ministries is undoubtedly a laudable step, this must be done in addition to prescribing mandatory rules, and not in place of it. Therefore, Rule 15(1) contravenes the provisions and legislative intent of the RPWD Act and is thus ultra vires, the Act."

Conclusions

Concluding, the Court said several of the guidelines prescribed in Rule 15, "appear to be recommendatory guidelines, under the garb of mandatory rules." It held Rule 15(1) to be ultra vires the scheme and legislative intent of the RPwD Act which creates a mechanism for mandatory compliance. "Creating a minimum floor of accessibility cannot be left to the altar of 'progressive realization'.

The Union Government was directed to delineate mandatory rules, as required by Section 40 of the RPwD Act, within a period of three months from the date of this Judgment. This exercise may involve segregating the non-negotiable rules from the expansive guidelines already prescribed in Rule 15 and the Union Government must conduct this exercise in consultation with all stakeholders, including NALSAR- CDS. The Court clarified that progressive compliance with the standards listed in the existing Rule 15(1) and the progress towards the targets of the Accessible India Campaign "must continue unabated. However, in addition, a baseline of non-negotiable rules must be prescribed in Rule 15."

Once the Union Government prescribes mandatory rules, the Union of India, States and Union Territories must ensure that the consequences prescribed in Sections 44, 45, 46 and 89 of the RPWD Act, including the holding back of completion certificates and imposition of fines are implemented in cases of non-compliance with Rule 15. The Union Government was directed to meaningfully consider the recommendations given by NALSAR-CDS while reworking the content of Rule 15.

The Court formulated four principles of accessibility that should be considered while carrying out the above exercise:

1. Universal Design: The rules should prioritize universal design principles, making spaces and services usable by all individuals to the greatest extent possible, without requiring adaptations or specialized design;

2. Comprehensive Inclusion Across Disabilities: Rules should cover a wide range of disabilities including physical, sensory, intellectual, and psychosocial disabilities. This includes provisions for specific conditions such as autism, cerebral palsy, intellectual disabilities, psychosocial disabilities, sickle cell disease, and ichthyosis;

3. Assistive Technology Integration: Mandating the integration of assistive and adaptive technologies, such as screen readers, audio descriptions, and accessible digital interfaces, to ensure digital and informational accessibility across public and private platforms; and

4. Ongoing Stakeholder Consultation: This process should involve continuous consultation with persons with disabilities and advocacy organizations to incorporate lived experiences and practical insights.

As NALSAR-CDS had stated that the report was prepared using their own resources, and no financial claims were made to the Ministry of Social Justice and Empowerment, the Court directed the Ministry to pay them an amount of Rs. 50 lakh as compensation for the work, "which was carried out in a timely and comprehensive manner." The amount is to be disbursed to NALSAR-CDS no later than 15 December 2024.

The Court adjourned the Writ Petition to 7 March 2025 on which date, the Union Government must report compliance to the Court.

Cause Title: Rajive Raturi v. Union of India [Writ Petition (C) No. 228 of 2006]

Click here to read/download the Judgment