If The Resultant Recovery Is Unimpeachable, The Conviction Of The Accused Can Be Based On Disclosure Statements: Supreme Court

|

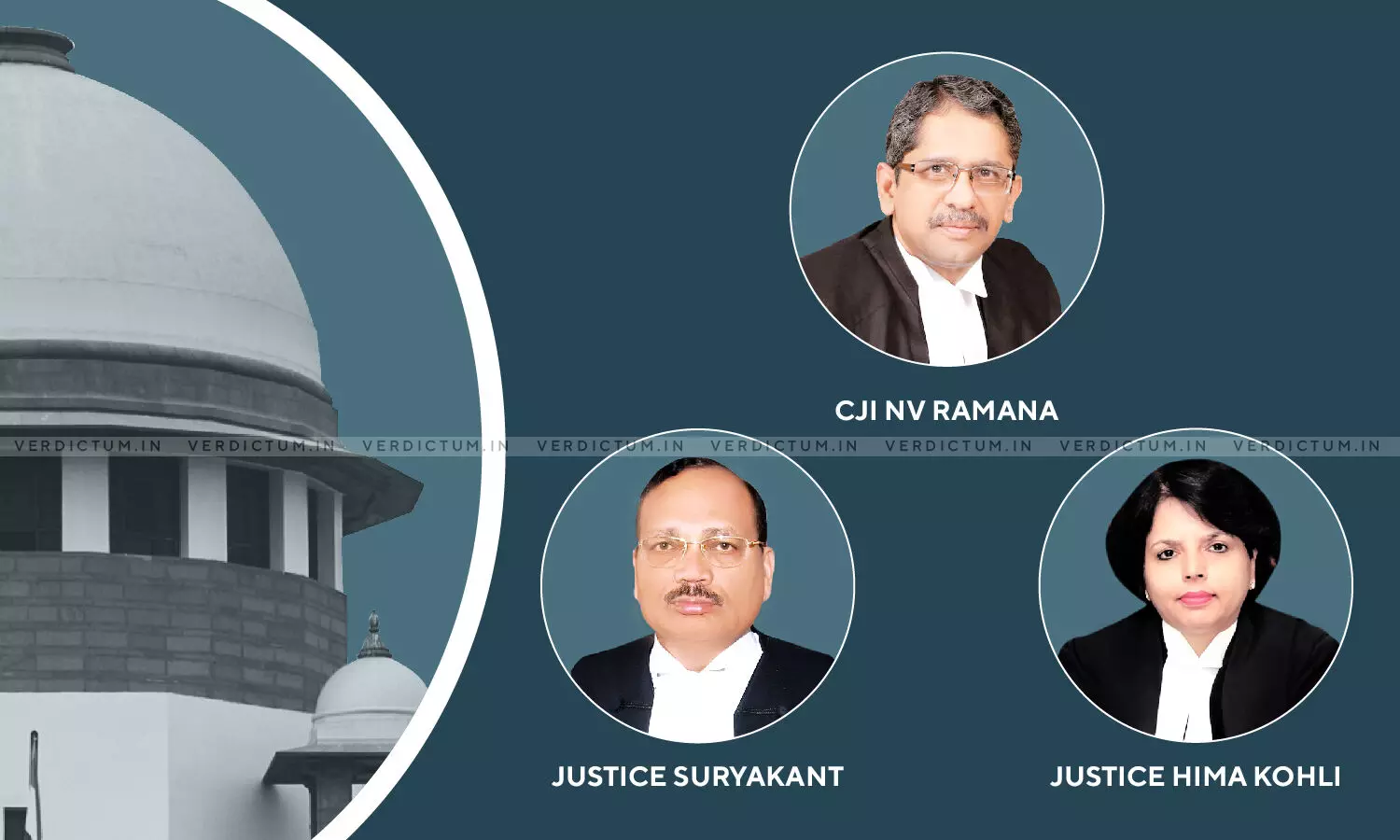

|A three-judge Bench of CJI NV Ramana, Justice Surya Kant and Justice Hima Kohli has held that at times the Court can convict an accused exclusively on the basis of disclosure statements and the resultant recovery of inculpatory material. However, such a conviction would sustain only if the resultant recovery is unimpeachable without any element of doubt.

An appeal was preferred by the Appellant-Accused against his order of conviction passed by the Punjab and Haryana High Court at Chandigarh which had affirmed the decision of the Additional Sessions Judge, Sonipat convicting the Appellant-Accused under Section 392 and Section 397 of IPC.

The High Court had upheld the conviction under Section 392 of sentencing the accused to 5 years rigorous imprisonment along with a fine of Rs. 5000. But the Court had reduced the conviction under Section 397 IPC from 10 years to 7 years rigorous imprisonment with a fine of Rs. 10,000.

In this case, it was alleged that the Appellant-Accused had committed offence under Sections 392 and 397 IPC and looted the Complainant of Rs. 46,000. This was followed by the arrest of the Appellant along with other co-accused and was charged under Sections 392, 397, and 120-B IPC and Section 25 of the Arms Act. The Appellant and the other co-accused had abjured their guilt and pleaded 'not guilty.'

The Prosecution had relied heavily upon the disclosure statements made by the accused persons and the pre-trial recoveries.

The main contention of the Appellant was that his conviction was solely based on the disclosure statements and there was no other substantial evidence to withstand his conviction under Sections 392 and 397 IPC. It was also argued that the Court had already acquitted two other co-accused involved in the case as there was a lack of evidence to sustain their conviction under Section 120-B of IPC.

The issue which was dealt with by the Court was whether the conviction of the Appellant on the strength of the purported disclosure statement and the recovery memo in the absence of any corroborative evidence could sustain.

The Apex Court noted that the only eyewitnesses to the alleged crime i.e., the Complainant (PW4) and his nephew (PW6) did not support the case of the Prosecution. The Complainant had denied that the Appellant or his co-accused were involved in the execution of the offence.

The Court held that there are circumstances and factors which help in calculating the intrinsic evidentiary value and credibility of the resultant recovery, which are – i) the period of interval between the malfeasance and the disclosure; ii) commonality of the recovered object and its availability in the market; iii) nature of the object and its relevance to the crime; iv) ease of transferability of the object; v) the testimony and trustworthiness of the attesting witness before the Court.

"Where the prosecution fails to inspire confidence in the manner and/or contents of the recovery with regard to its nexus to the alleged offence, the Court ought to stretch the benefit of doubt to the accused," the Bench opined.

Further, the Court relied upon the cardinal principle of criminal jurisprudence and held, "It is better that ten guilty persons escape, than that one innocent suffer."

"It is the bounden duty of the prosecution in cases where material witnesses are likely to be slippery, either to get their statements recorded at the earliest under Section 164 Cr.P.C. or collect such other cogent evidence that its case does not entirely depend upon oral testimonies," asserted the Court.

The Court also gave the following observations holding that that both the High Court and Trial Court hastened to shift the burden on the Accused to elucidate how was he in possession of the incriminating articles without primarily scrutinizing the credibility and admissibility of the recovery as well as its linkage to the misconduct –

i) Both the Courts failed to notice that no effort was made by the Police to conduct a search of Appellant's residence in the presence of local witnesses;

ii) Denial by the Complainant in supporting the case of Prosecution;

iii) Complainant negated his signatures on recovery memo;

iv) Recovered articles easily available in the market;

v) Recovery took place after a month of commission of the alleged offence; and

vi) No other evidence on record which proved the iniquity of Appellant.

The Court further observed, "The evidence on record does not establish the guilt of the Appellant beyond reasonable doubt and the Courts below have arrived at recording the guilt of the Appellant in absence of any cogent rationale, justifying his conviction."

In the light of these observations, the Court acquitted the Appellant, allowed the appeal, and set aside and quashed the judgment of the High Court and the Trial Court.