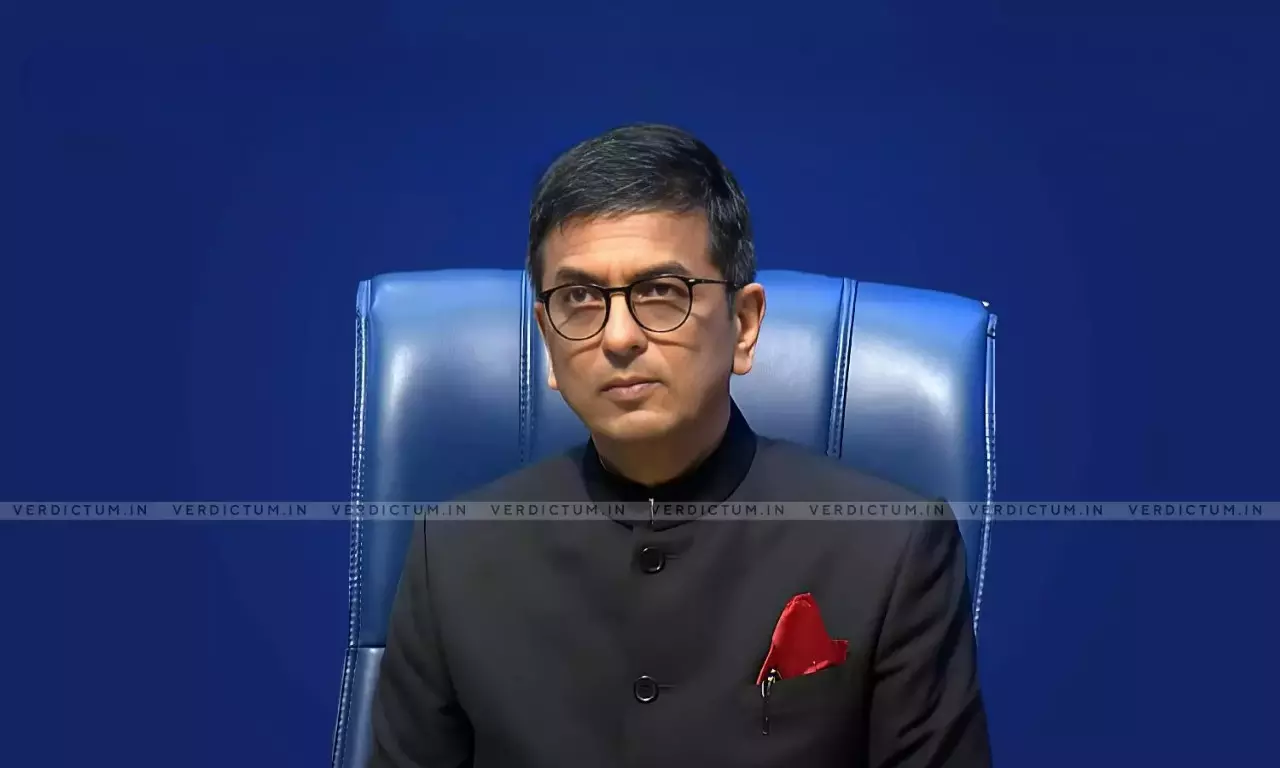

Court Must Not Use Judicial Power To Push Through Collegium Recommendations: Former CJI Chandrachud

|

|In an interview, the recently retired Chief Justice of India Dr. D.Y. Chandrachud said that the judiciary should not take up the issue of appointments of Judges on the judicial side, cautioning against using judicial power to force through Collegium recommendations.

Justice Chandrachud also defended the visit of the Prime Minister to his official residence for prayers, stating that meetings between the executive and the judiciary, whether social or otherwise, are routine occurrences.

Court is only one stakeholder in appointments

A diversity of stakeholders are involved in the appointment of Judges, he began by saying, and since "we are a federal country, the very process of appointments is not as simple as it would be in a unitary political system."

Revealing that he has "very strong reservations" about taking the issue of appointments on the judicial side, he reasoned that the Supreme Court is only one of the stakeholders in the process of appointment "albeit an important stakeholder."

"If we use our judicial power to ensure that persons whom we recommend are appointed we would be then using judicial power to implement essentially what are our Constitutional recommendations by the collegium which I have reservations about." He recommended that there should be "a sense of robust dialogue" between the government and the judiciary and if the government has certain reservations on the appointment of a person as a Judge "we must understand what those reservations are."

Justice Chandrachud said, "Sometimes those reservations may be quite justified, at other times they may not be justified", adding that there have been examples on both ends of the spectrum and in cases where the Collegium found the government's objections to be unjustified, names have been reiterated.

Even Judiciary has a veto

The former CJI said that there has to be a sense of robust dialogue between the government and the Judiciary and that if the government has certain reservations on an appointment, the judiciary must understand what those reservations are.

"Sometimes those reservations may be quite justified, at other times they may not be justified. So we had examples on both ends of the spectrum. Where we have found that those reservations are not justified, we have reiterated those recommendations. Equally, it is important to understand that in the Collegium System, it is not just the government which has a veto, the Judiciary as well has a veto. A judge whom the Collegium does not find fit for appointment to the Judiciary can never become a judge. So, it shows that there are checks and balances", Justice Chandrachud said in the interview given to CNN-News 18.

A Judge does not have to be atheist to be impartial

The dialogue between the executive and the judiciary and the larger issue of separation of powers also cropped up when Justice Chandrachud was asked whether only atheist judges could be seen as impartial and the correctness of the opinion that judges are biased against the religion to which they belong.

Justice Chandrachud answered, "For a Judge to be impartial, he does not have to be an atheist." Judges are citizens and humans too and are entitled to the same fundamental rights as others, "in fact, the fact that we're humans ensures that we understand the problems of other human beings." He was of the firm view that "individual beliefs of judges have nothing to do with how they decide cases" because by training Judges are expected to decide cases in accordance with the law and in accordance with the Constitution.

Justice Chandrachud said if the argument that only an atheist judge can be truly impartial is to be accepted, then it can be applied across the board, to region, to culture, to language, and gender. He rhetorically asked the interviewer, "Why confine this to religion? Can we say that a only woman judge who can understand or do justice in a case involving women? Obviously not. Can we say that only a judge having a particular sexuality can do justice on that category bearing on sexuality? Obviously not. Judges, by training, are taught to be and expected to be diverse in our approach."

On the controversy surrounding his admission that he had engaged in prayers before delivering the Judgement in the Ayodhya dispute, he asserted that he is not "hypocritical enough to conceal that I am a man of faith and I believe that my faith has nothing to do with my ability to dispense justice."

PMs meet Judges on various occasions

Justice Chandrachud was then asked about the invitation to Prime Minister Narendra Modi for Ganpati prayers and its propriety in view of the ideal of detachment between the executive and the judiciary. Chandrachud said that there have always been dialogues between the two organs, for instance between Chief Ministers and Chief Justices of the High Courts. "You may be meeting for a particular issue like the infrastructure of the High Court or you may be meeting on a social occasion. Our system does have a sense of political maturity that this dialogue does not impinge on the judicial work that we do."

Giving an example of interactions between the judiciary and the executive, Justice Chandrachud said, as the Chief Justice of India, he met the Minister of Law and Justice "very frequently" to ensure that the Collegium's recommendations were followed through. "The sense of dialogue per se is not contrary to judicial independence. It is essential to ensure that the affairs of the State and governance are duly carried on with a sense of efficiency."

On the particular incident of the Prime Minister's visit to his official residence, he said, "Prime Ministers are known to visit the homes of Judges on various occasions. Social occasions, sometimes happy occasions, sometimes difficult occasions."

"Can you pinpoint a single instance where the outcome of a case was deflected because there was a dialogue between the judiciary and the executive? Obviously no." Justice Chandrachud contended. "Both before and after that visit, I believe no one can (cite) a single case where it could be remotely suggested that that visit affected the outcome of a case."