A Decision Is Per Incuriam Only When Overlooked Statutory Provision Or Legal Precedent Is Central To Legal Issue: Supreme Court

The Supreme Court observed that a decision is per incuriam only when the overlooked statutory provision or legal precedent is central to the legal issue in question and might have led to a different outcome if those overlooked provisions were considered.

The Court observed thus in a civil appeal preferred by M/s Bajaj Alliance General Insurance Co. Ltd. A Constitution Bench clarified in this case that a person holding a license to drive a ‘light motor vehicle’ (LMV) would be automatically entitled to drive a light transport vehicle with an unladen weight of 7500 kilograms.

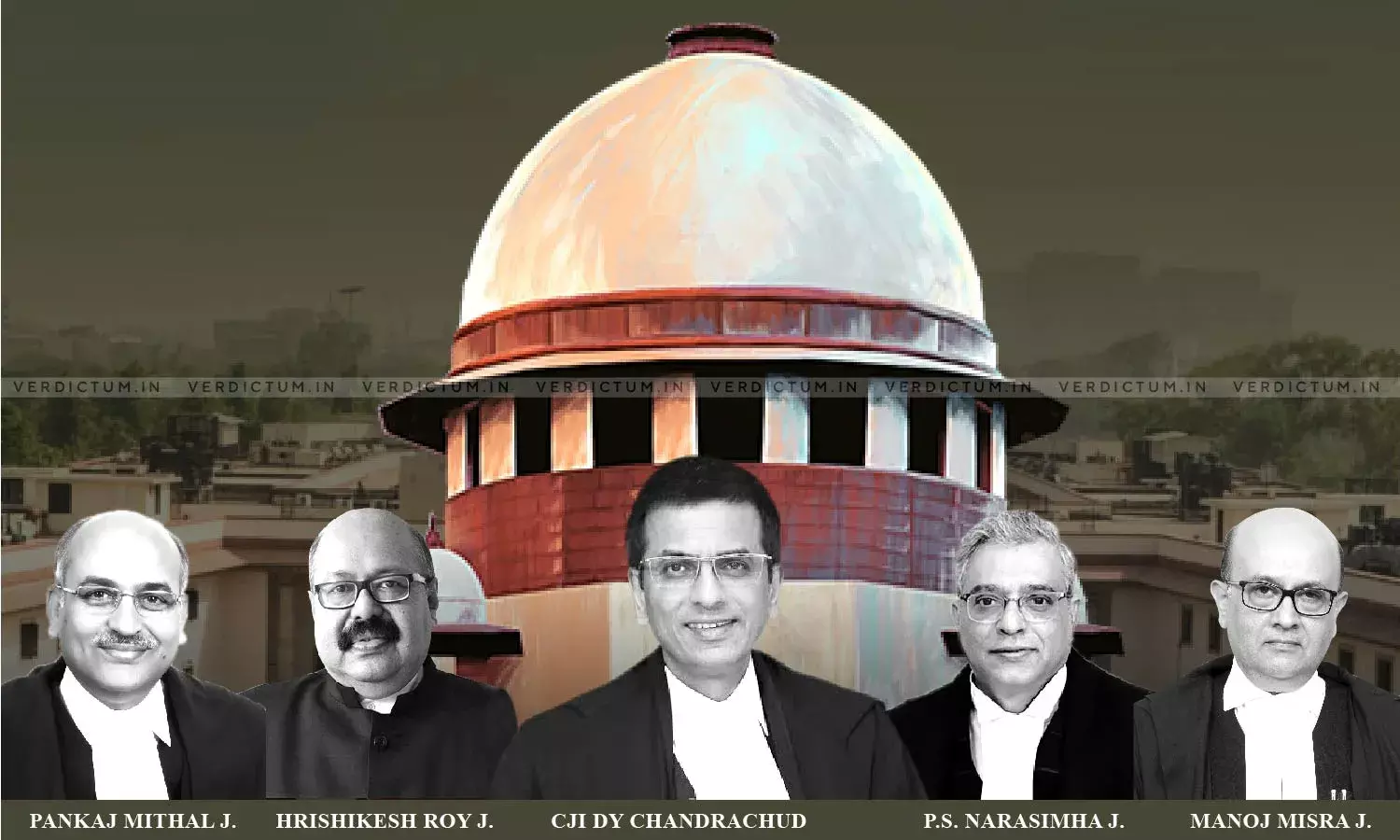

The five-Judge Bench comprising CJI D.Y. Chandrachud, Justice Hrishikesh Roy, Justice P.S. Narasimha, Justice Pankaj Mithal, and Justice Manoj Misra held, “… when dealing with the ignorance of a statutory provision, we may bear in mind the following principles. These may not however be exhaustive:

(i) A decision is per incuriam only when the overlooked statutory provision or legal precedent is central to the legal issue in question and might have led to a different outcome if those overlooked provisions were considered. It must be an inconsistent provision and a glaring case of obtrusive omission.

(ii) The doctrine of per incuriam applies strictly to the ratio decidendi and does not apply to obiter dicta.

(iii) If a court doubts the correctness of a precedent, the appropriate step is to either follow the decision or refer it to a larger Bench for reconsideration.

(iv) It has to be shown that some part of the decision was based on a reasoning which was demonstrably wrong, for applying the principle of per incuriam. In exceptional instances, where by obvious inadvertence or oversight, a judgment fails to notice a plain statutory provision or obligatory authority running counter to the reasoning and result reached, the principle of per incuriam may apply.”

Solicitor General Tushar Mehta, Senior Advocates Siddhartha Dave, Jayant Bhushan, Archana Pathak Dave, Neeraj Kishan Kaul, Advocates Amit Kumar Singh, and Shivam Singh appeared for the appellant while Senior Advocate Anitha Shenoy, Advocates Devvrat, Kaustubh Shukla, and Anuj Bhandari appeared for the respondents.

Factual Background -

The then two-Judge Bench of Justice Kurian Joseph and Justice Arun Mishra dealt with the case of Mukund Dewangan v. Oriental Insurance Co. Ltd. (2016) 4 SCC 298 in which it took note of the conflicting views in 8 different judgments of the Apex Court and framed some questions for determination by a three-Judge Bench. Speaking through Justice Arun Mishra, the reference was answered by a 3-Judge Bench of Justice Arun Mishra, Justice Amitava Roy, and Justice Sanjay Kishan Kaul in Mukund Dewangan v. Oriental Insurance Co. Ltd. (2017) 14 SCC 663. The Bench concluded that the holder of a license for a ‘Light Motor Vehicle’ class need not have a separate endorsement to drive a ‘transport vehicle’ if it falls under the ‘Light Motor Vehicle’ class i.e. below 7,500 kgs. However, this pronouncement did not put the matter to rest and in M/s. Bajaj Alliance General Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Rambha Devi & Ors. (2019) 12 SCC 816, the Court noted that while deciding the vexed question in Mukund Dewangan (2017), the 3 Judge-bench had not considered important provisions of the Motor Vehicles Act, 1988 (MV Act) and MV Rules.

The Court referred the prayer itself for reconsideration of the ratio in Mukund Dewangan 2017 Case to a larger bench. The 3-judge bench flagged certain additional provisions that were not noticed in Mukund Dewangan (2017) and since such a view was expressed by a Bench of equal strength, it was considered appropriate to refer the matter to a larger bench of five judges. Thus, the correctness of Mukund Dewangan (2017) was to be evaluated during this reference. In view of the consultative exercise being carried out by the government, the matter was deferred multiple times.

The Supreme Court in the above context of the case, noted, “In a recent decision in Shah Faesal v. Union of India61, a five judge bench of this Court reiterated that the principle of per incuriam only applies on the ratio of the case.”

The Court said that the overlooked provisions would not alter the eventual pronouncement and therefore, the ratio in Mukund Dewangan (2017) should not be disturbed by applying the principles of per incuriam.

“The dangers of reasoning without empirical data 64 and beyond the statutory scheme of the Act must be avoided. While we are mindful of issues of road safety, the task of crafting policy lies within the domain of the legislature. As a constitutional court, it is not our role to dictate policy decisions or rewrite laws. We must be mindful of the institutional limitation to address such concerns”, it added.

Furthermore, the Court observed that, had the Parliament acted sooner to amend the MV Act and clearly differentiated between classes, categories and types, much of the uncertainty surrounding driving licenses could have been addressed, reducing the need for frequent litigation and an unclear legal terrain.

“The confusion and inconsistency in judicial decisions continued to persist for 25 years starting from the 1999 decision in Ashok Gangadhar Maratha(supra). … Road safety is a serious public health issue globally. It is crucial to mention that in India, over 1.7 lakh persons were killed in road accidents in 2023. The causes of such accidents are diverse, and assumptions that they stem from drivers operating light transport vehicles with an LMV license are unsubstantiated”, it remarked.

The Court also noted that the factors contributing to road accidents include careless driving, speeding, poor road design, and failure to adhere to traffic laws and other significant contributors are mobile phone usage, fatigue, and non-compliance with seat belt or helmet regulations.

“The licensing regime under the MV Act and the MV Rules, when read as a whole, does not provide for a separate endorsement for operating a ‘Transport Vehicle’, if a driver already holds a LMV license. We must however clarify that the exceptions carved out by the legislature for special vehicles like e-carts and e-rickshaws, or vehicles carrying hazardous goods, will remain unaffected by the decision of this Court”, it emphasised.

Moreover, it said that the Court must ensure that neither provision i.e. the definition under Section 2(21) nor the second part of Section 3(1) which concerns the necessity for a driving license for a ‘Transport Vehicle’ is reduced to a dead letter of law and therefore, the emphasis on ‘Transport Vehicle’ in the licensing scheme has to be understood only in the context of the ‘medium’ and ‘heavy’ vehicles.

“In an era where autonomous or driver-less vehicles are no longer tales of science fiction and app-based passenger platforms are a modern reality, the licensing regime cannot remain static. The amendments that have been carried out by the Indian legislature may not have dealt with all possible concerns. As we were informed by the Learned Attorney General that a legislative exercise is underway, we hope that a comprehensive amendment to address the statutory lacunae will be made with necessary corrective measures”, it added.

The Court, therefore, concluded the following important points –

(I) A driver holding a license for Light Motor Vehicle (LMV) class, under Section 10(2)(d) for vehicles with a gross vehicle weight under 7,500 kg, is permitted to operate a ‘Transport Vehicle’ without needing additional authorization under Section 10(2)(e) of the MV Act specifically for the ‘Transport Vehicle’ class. For licensing purposes, LMVs and Transport Vehicles are not entirely separate classes. An overlap exists between the two. The special eligibility requirements will however continue to apply for, inter alia, e-carts, e-rickshaws, and vehicles carrying hazardous goods.

(II) The second part of Section 3(1), which emphasizes the necessity of a specific requirement to drive a ‘Transport Vehicle,’ does not supersede the definition of LMV provided in Section 2(21) of the MV Act.

(III) The additional eligibility criteria specified in the MV Act and MV Rules generally for driving ‘transport vehicles’ would apply only to those intending to operate vehicles with gross vehicle weight exceeding 7,500 kg i.e. ‘medium goods vehicle’, ‘medium passenger vehicle’, ‘heavy goods vehicle’ and ‘heavy passenger vehicle’.

(IV) The decision in Mukund Dewangan (2017) is upheld but for reasons as explained by us in this judgment. In the absence of any obtrusive omission, the decision is not per incuriam, even if certain provisions of the MV Act and MV Rules were not considered in the said judgment.

Accordingly, the Apex Court answered the reference.

Cause Title- M/s Bajaj Alliance General Insurance Co. Ltd. v. Rambha Devi & Ors. (Neutral Citation: 2024 INSC 840)