Prosecution Witnesses' Statement During Trial Regarding Involvement Of Accused Cannot Be Relied Upon If They Had Failed To Mention It In Their Statements U/S 161 CrPC: SC

The Supreme Court held that witnesses' testimonies during trial proceedings regarding an accused's involvement cannot be relied upon if the same was not previously stated in their statements under Section 161 of the Criminal Procedure Code, 1973 (CrPC).

The Court acquitted a murder convict and allowed a Criminal Appeal filed by him challenging concurrent convictions.

The Court emphasized that the introduction of new facts during the trial is impermissible.

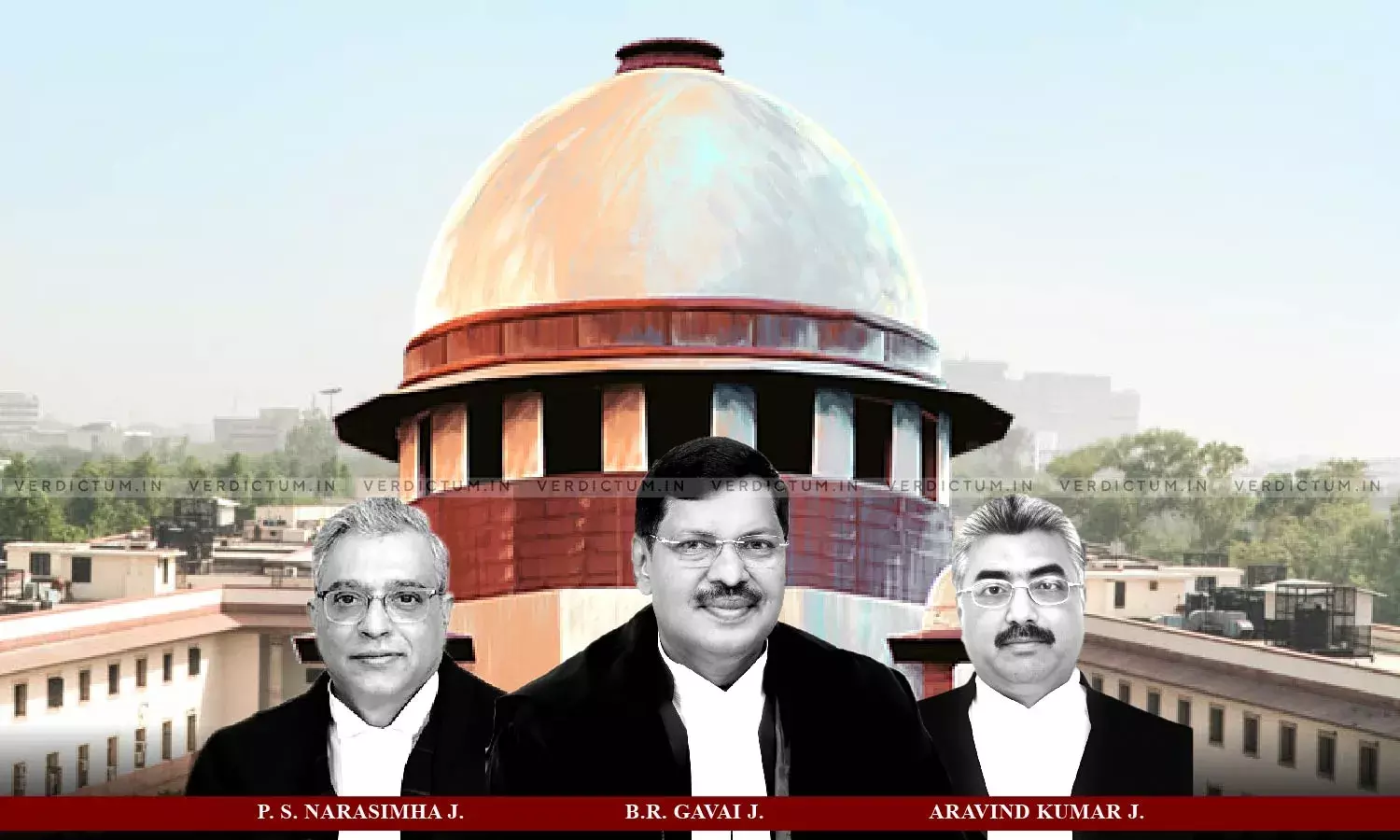

The Bench comprising Justice B. R. Gavai, Justice P. S. Narasimha and Justice Aravind Kumar observed, “if the PWs had failed to mention in their statements u/s 161 CrPC about the involvement of an accused, their subsequent statement before court during trial regarding involvement of that particular accused cannot be relied upon. Prosecution cannot seek to prove a fact during trial through a witness which such witness had not stated to police during investigation. The evidence of that witness regarding the said improved fact is of no significance”.

Advocate Abhimanyu Tewari appeared for the Appellant and Advocate Prateek Chaddha appeared for the State.

A Criminal Appeal was filed challenging the High Court's judgment that upheld the conviction and sentence of the Appellant while acquitting the co-accused.

The Appellant and the co-accused were involved in a romantic relationship and were indicted for the murder of the Appellant’s wife by poisoning. Per the prosecution’s case, on the night of May 18, 1999, and May 19, 1999, the Appellant with the co-accused intentionally administered poison to eliminate the Appellant’s Wife. Both were charged under Sections 302 and 34 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC), and the Trial Court convicted and sentenced them to life imprisonment. However, the High Court acquitted the co-accused, based on the testimonies of Prosecution witnesses (PW) no 3 & 4.

The Court observed that the prosecution, lacking direct eyewitness testimony, depended on circumstantial evidence, requiring the construction of a comprehensive chain of circumstances to establish guilt beyond reasonable doubt.

Furthermore, the Bench noted that the pivotal circumstance centred around the presence of the Appellant and the co-accused in the Appellant's house on a pertinent night, invoking Section 106 of the Evidence Act. This proof of presence is crucially tied to the Appellant's opportunity to administer poison.

“Secondly, the appellant would be under a duty to explain as to the circumstances that led to the death of the deceased. In that sense, there is a limited shifting of the onus of proof. If he remains quiet or offers a false explanation, then such a response would become an additional link in the chain of circumstances”, the Bench added.

The Bench noted that PW-3 testified that her husband, PW-4, informed her about seeing the appellant and co-accused in the appellant's house on May 18, 1999, expressing concern about potential family conflict. He advised against visiting, suggesting discussing it in the morning. The next day, PW-3 found her sister dead in the appellant's house, with both the appellant and co-accused present, pushing her aside before leaving in a jeep.

In cross-examination, the Court observed omissions in PW-3's Section 161 CrPC statement, including her husband's details and advice. She claimed to witness the appellant and co-accused administering poison. Discrepancies in PW-4's statement were highlighted.

The Bench highlighted the unreliability of trial testimonies introducing facts that were not stated to the police during the investigation. The Court criticized the High Court for inconsistently relying on PW-3 and PW-4's testimonies, noting the error in accepting the Appellant's presence while dismissing the co-accused's presence at the Appellant’s house at the time of the incident.

The Court, while expressing reservations about the definite occurrence of a homicide, observed that the presented evidence, even under the assumption of the Accused's presence, does not eliminate the possibility of suicide.

"Further, this Court has previously considered the consequences when a particular defence plea was not taken by accused u/s 313 CrPC and held that mere omission to take a specific plea by accused when examined u/s 313 CrPC, is not enough to denude him of his right if the same can be made out otherwise", the Court added.

The Bench observed that, according to the prosecution, both the Appellant and co-accused were jointly present in the Appellant's house on the night of May 18, 1999, and were seen leaving together on May 19, 1999, after administering poison to the deceased.

Additionally, the Bench emphasised that despite being tried together, the High Court acquitted the co-accused due to doubts about her presence. However, the High Court for not extending the same benefit of doubt to the Appellant, reasoning that, as the husband, his presence was natural.

"If the presence of co-accused in the house on the date of the alleged incident is doubtful, then, the testimony of PW 5 that he had seen her along with the appellant in the jeep, will also lose its strength", the Court noted. The Apex Court found the High Court's distinction between the Appellant's and the co-accused cases to be perverse and unconvincing.

Due to doubts about the Accused's presence, the Apex Court deemed it unnecessary to consider other circumstances presented by the prosecution. The Bench held that in cases relying solely on circumstantial evidence, any gap or the possibility of an alternative reasonable explanation entitles the Accused to the benefit of the doubt.

Accordingly, the Court allowed the Appeal and Set aside the impugned judgment of conviction.

Cause Title: Darshan Singh v State Of Punjab (2024 INSC 19)