Death Penalty Can Only Be Awarded In Rarest Of Rare Cases With No Possibility Of Reformation- SC Commutes Sentence In Murder Case

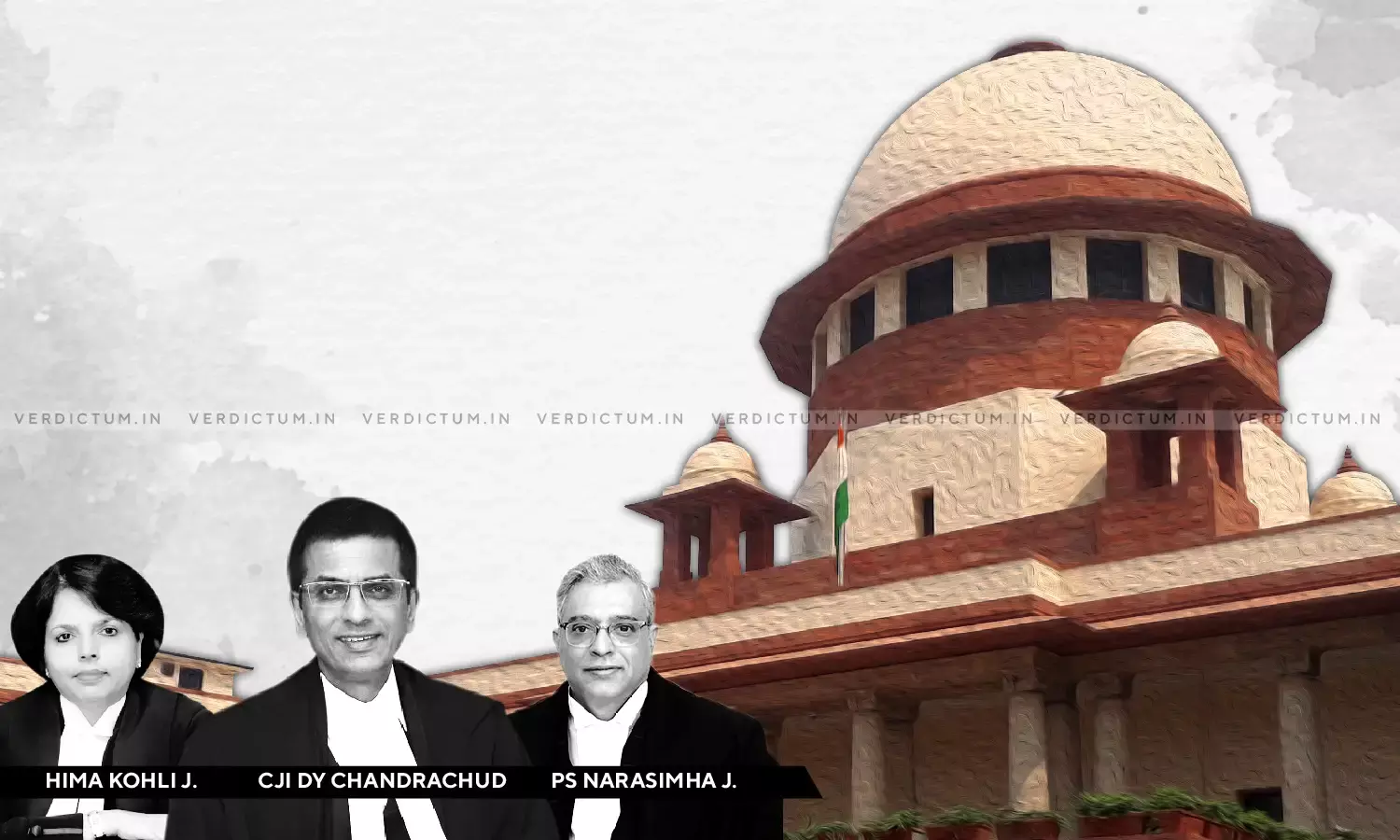

A Supreme Court Bench of Chief Justice Dhananjaya Y Chandrachud, Justice Hima Kohli, and Justice Pamidighantam Sri Narasimha has commuted the death sentence awarded for the kidnapping and murder of a 7-year-old child to life imprisonment for not less than 20 years, without remission.

The Court held that "even though the crime committed by the petitioner is unquestionably grave and unpardonable, it is not appropriate to affirm the death sentence that was awarded to him. As we have discussed, the ‘rarest of rare’ doctrine requires that the death sentence not be imposed only by taking into account the grave nature of crime but only if there is no possibility of reformation in a criminal."

Counsel Renjith B appeared for the Petitioner, while Counsel Joseph Aristotle S appeared for the State.

In this case, the applicant was a convict on death row, who moved to the Supreme Court for a fresh look at his petition seeking a review of his conviction for the offence of murder and the award of the death sentence. The petitioner had kidnapped and murdered a 7-year-old child.

The Supreme Court reiterated that no reasonable doubt was raised in the prosecution's case. It also observed that there was no "lingering doubt" and that the relevant standard to confirm the guilt of the petitioner had been applied.

However, the Apex Court relied on a catena of Judgments like Dagdu v State of Maharashtra, and observed that a meaningful, real and effective hearing was not afforded to the petitioner. In that context, it was said that "The Trial Court did not conduct any separate hearing on sentencing and did not take into account any mitigating circumstances pertaining to the petitioner before awarding the death penalty."

Examining the orders passed by the lower courts, the Apex Court observed that while the gruesome and merciless nature of the act was taken into cognisance, no mitigating circumstances of the petitioner were taken into account at any stage of the trial or the appellate process, even though the petitioner was sentenced to capital punishment.

Notably, the Apex Court was unappreciative of considering an aggravating circumstance based on the sex of the child. In that context, the Supreme Court said that "the sex of the child cannot be in itself considered as an aggravating circumstance by a constitutional court. The murder of a young child is unquestionably a grievous crime and the young age of such a victim as well as the trauma that it causes for the entire family is in itself, undoubtedly, an aggravating circumstance. In such a circumstance, it does not and should not matter for a constitutional court whether the young child was a male child or a female child. The murder remains equally tragic. Courts should also not indulge in furthering the notion that only a male child furthers family lineage or is able to assist the parents in old age. Such remarks involuntarily further patriarchal value judgements that courts should avoid regardless of the context."

Further, the Court relied on the law laid down in Bachan Singh, which requires meeting the standard of "rarest of rare" for the award of the death penalty, which requires the Court to conclude that the convict is not fit for any reformatory and rehabilitation scheme. In that context, the Court observed that "No such inquiry has been conducted for enabling a consideration of the factors mentioned above in case of the petitioner. Neither the trial court, nor the appellate courts have looked into any factors to conclusively state that the petitioner cannot be reformed or rehabilitated."

The Court noted that "the conduct of petitioner has been satisfactory and he has not been involved in any other case. Furthermore, he is suffering from systemic hypertension and availing medication from the prison hospital. The petitioner has also acquired a diploma in food catering during his time in the prison."

Further, the Court noted that the petitioner could not communicate mitigating circumstances bearing on his sentencing decision to the lawyer and his relatives, who being poor and uneducated, could not properly contest the case for him.

Consequently, the Court held that "it cannot be said that there is no possibility of reformation even though the petitioner has committed a ghastly crime. We must consider several mitigating factors: the petitioner has no prior antecedents, was 23 years old when he committed the crime and has been in prison since 2009 where his conduct has been satisfactory, except for the attempt to escape prison in 2013. The petitioner is suffering from a case of systemic hypertension and has attempted to acquire some basic education in the form of a diploma in food catering. The acquisition of a vocation in jail has an important bearing on his ability to lead a gainful life."

In similar context, the Court took the view that "we are of the view that even though the crime committed by the petitioner is unquestionably grave and unpardonable, it is not appropriate to affirm the death sentence that was awarded to him. As we have discussed, the ‘rarest of rare’ doctrine requires that the death sentence not be imposed only by taking into account the grave nature of crime but only if there is no possibility of reformation in a criminal."

Therefore, the Court held that the petitioner must undergo life imprisonment for not less than twenty years without remission of sentence.

Cause Title: Sundar @ Sundarrajan v. State by Inspector of Police

Click here to read/download the Judgment