Curative Jurisdiction May Be Invoked If There Is A Miscarriage Of Justice: Supreme Court Allows DMRC’s Curative Petition Against DAMEPL

The Supreme Court allowed the curative petition of Delhi Metro Rail Corporation Ltd. (DMRC) against Delhi Airport Metro Express Pvt. Ltd. (DAMEPL) and set aside its judgment in the case of Delhi Airport Metro Express Private Limited v. Delhi Metro Rail Corporation Ltd. (2022) 1 SCC 131.

The Court said that curative jurisdiction may be invoked if there is a miscarriage of justice.

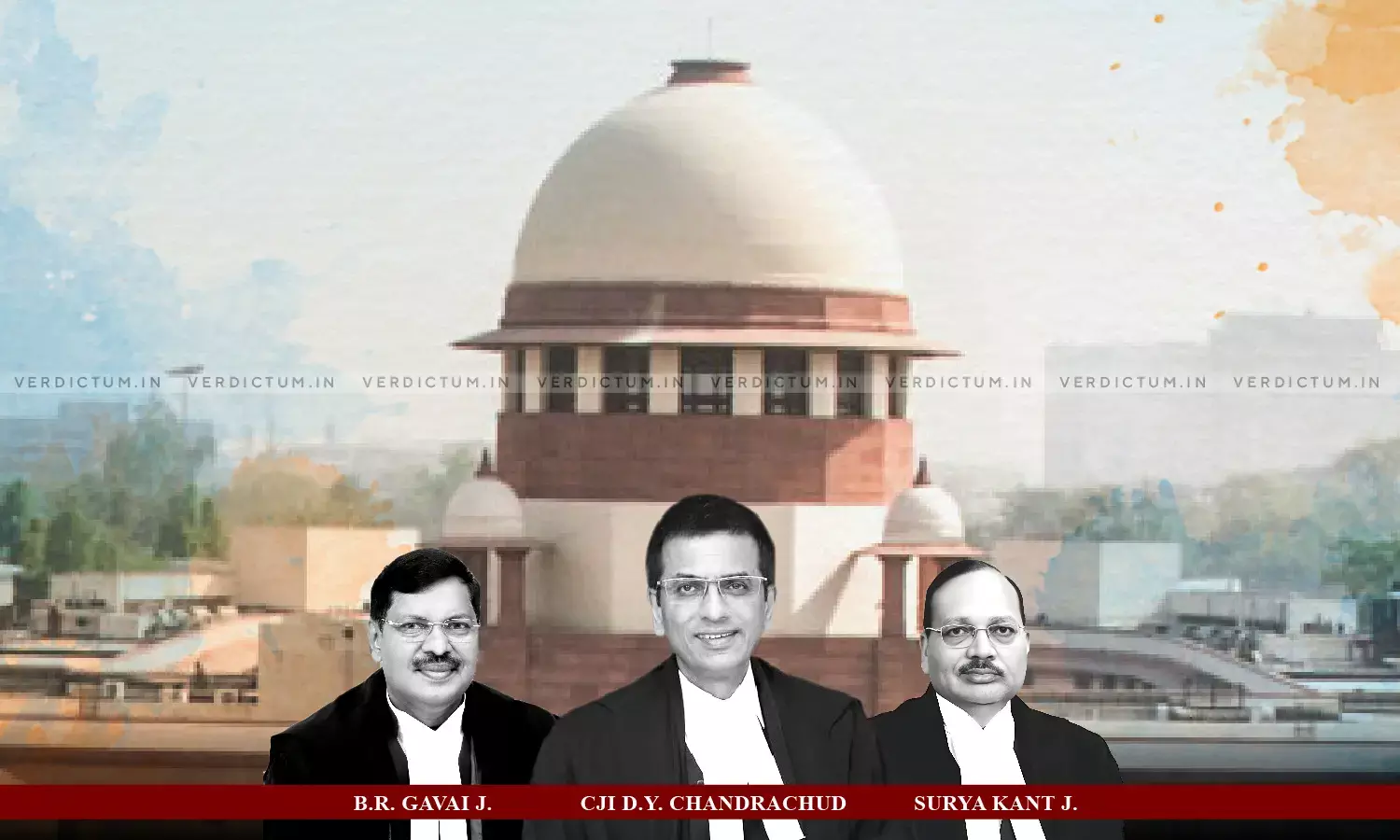

The three-Judge Bench comprising CJI D.Y. Chandrachud, Justice B.R. Gavai, and Justice Surya Kant observed, “The enumeration of the situations in which the curative jurisdiction can be exercised is thus not intended to be exhaustive. … In essence, the jurisdiction of this Court, while deciding a curative petition, extends to cases where the Court acts beyond its jurisdiction, resulting in a grave miscarriage of justice. We now proceed to lay down the scope of jurisdiction of this Court and the competent courts below while dealing with cases arising out of an application to set aside an arbitral award under Section 34 of the Arbitration Act.”

Attorney General R Venkataramani, Senior Advocates K.K. Venugopal, Parag Tripathi, and Maninder Singh represented the petitioner while Senior Advocates Harish Salve, Kapil Sibal, J.J. Bhatt, and Prateek Seksaria represented the respondent.

Brief Facts -

The petitioner, DMRC was a state-owned company wholly owned by the Indian Government and the National Capital Territory of Delhi. The respondent, DAMEPL was a special-purpose vehicle incorporated by a consortium comprising Reliance Infrastructure Limited and Construcciones Y Auxiliar de Ferrocarriles SA, Spain. The consortium bagged the contract for the construction, operation, and maintenance of the Delhi Airport Express Ltd. in 2008. The Concession Agreement envisaged a public-private partnership for providing metro rail connectivity between New Delhi Railway Station and Indira Gandhi International Airport and other points within Delhi. There was an exchange of correspondence between the parties which ultimately led the Ministry of Urban Development to convene a meeting of stakeholders in 2012. A Joint Inspection Committee was set up to inspect the defects alleged by DAMEPL.

Meanwhile, DAMEPL expressed its intention to halt operations, alleging that the line was unsafe to operate. Operations were stopped in 2012 and DAMEPL issued a notice to DMRC containing a ‘non-exhaustive’ list of eight defects which according to them, affected the performance of their obligations under the 2008 Agreement. The CMRS issued sanction in 2013 which was subject to certain conditions. Thereafter, the Arbitral Tribunal was constituted which passed a unanimous award in favour of DAMEPL. Hence, DMRC instituted an application under Section 34 of the Arbitration and Conciliation Act, 1996 (A&C Act) before the Single Bench of the Delhi High Court. The High Court dismissed the petition which gave rise to an appeal before the Division Bench. The appeal was partly allowed and DAMEPL moved a Special Leave Petition and the two-Judge Bench of the Supreme Court allowed the same and restored the award. The review petition assailing this decision was dismissed and thus, curative petition was filed.

The Supreme Court in view of the facts and circumstances of the case noted, “While adjudicating the merits of a Special Leave Petition and exercising its power under Article 136, this Court must interfere sparingly and only when exceptional circumstances exist, justifying the exercise of this Court’s discretion. The Court must apply settled principles of judicial review such as whether the findings of the High Court are borne out from the record or are based on a misappreciation of law and fact. In particular, this Court must be slow in interfering with a judgement delivered in exercise of powers under Section 37 unless there is an error in exercising of the jurisdiction by the Court under Section 37 as delineated above. Unlike the exercise of power under Section 37, which is akin to Section 34, this Court (under Article 136) must limit itself to testing whether the court acting under Section 37 exceeded its jurisdiction by failing to apply the correct tests to assail the award.”

The Court said that the award is unreasoned and it overlooks vital evidence in the form of the joint application of the contesting parties to CMRS and the CMRS certificate. It added that the arbitral tribunal ignored the specific terms of the termination clause and reached a conclusion which is not possible for any reasonable body of persons to arrive at and hence, the arbitral tribunal erroneously rejected the CMRS sanction as irrelevant.

“The award bypassed the material on record and failed to reconcile inconsistencies between the factual averments made in the cure notice, which formed the basis of termination on the one hand and the evidence of the successful running of the line on the other. The Division Bench correctly held that the arbitral tribunal ignored vital evidence on the record, resulting in perversity and patent illegality, warranting interference. The conclusions of the Division Bench are, thus, in line with the settled precedent including the decisions in Associate Builders (supra) and Ssangyong (supra)”, it further noted.

The Court, therefore, observed that the judgment of the two-judge Bench, which interfered with the judgment of the Division Bench of the High Court, has resulted in a miscarriage of justice and that it applied the correct test in holding that the arbitral award suffered from the vice of perversity and patent illegality. It said that the findings of the Division Bench were borne out from the record and were not based on a misappreciation of law or fact.

“This Court failed, while entertaining the Special Leave Petition under Article 136, to justify its interference with the well-considered decision of the Division Bench of the High Court. The decision of this Court fails to adduce any justification bearing on any flaws in the manner of exercise of jurisdiction by the Division Bench under Section 37 of the Arbitration Act. By setting aside the judgement of the Division Bench, this Court restored a patently illegal award which saddled a public utility with an exorbitant liability. This has caused a grave miscarriage of justice, which warrants the exercise of the power under Article 142 in a Curative petition, in terms of Rupa Hurra (supra)”, it held.

The Court ordered that the parties are restored to the position in which they were on the pronouncement of the judgement of the Division Bench and that the execution proceedings before the High Court for enforcing the arbitral award must be discontinued and the amounts deposited by the petitioner pursuant to the judgment of the Court shall be refunded. It directed that the part of the awarded amount, if any, paid by the petitioner as a result of coercive action is liable to be restored in favour of the petitioner.

“Before concluding, we clarify that the exercise of the curative jurisdiction of this Court should not be adopted as a matter of ordinary course. The curative jurisdiction should not be used to open the floodgates and create a fourth or fifth stage of court intervention in an arbitral award, under this Court’s review jurisdiction or curative jurisdiction, respectively. … In the specific facts and circumstances of this case to which we have adverted in the course of the discussion, we have come to the conclusion that this Court erred in interfering with the decision of the Division Bench of the High Court”, it said.

The Court added that the judgment of the Division Bench in the appeal under Section 37 of the A&C Act was based on a correct application of the test under Section 34 of the Act and that the judgment of the Division Bench provided more than adequate reasons to come to the conclusion that the arbitral award suffered from perversity and patent illegality. It noted that there was no valid basis for the Supreme Court to interfere under Article 136 of the Constitution.

“The interference by this Court has resulted in restoring a patently illegal award. This has caused a grave miscarriage of justice. We have applied the standard of a ‘grave miscarriage of justice’ in the exceptional circumstances of this case where the process of arbitration has been perverted by the arbitral tribunal to provide an undeserved windfall to DAMEPL”, it concluded.

Accordingly, the Apex Court allowed the curative petition.

Cause Title- Delhi Metro Rail Corporation Ltd. v. Delhi Airport Metro Express Pvt. Ltd. (Neutral Citation: 2024 INSC 292)