Constituent Assembly Didn’t Include ‘Socialist' & ‘Secular' In Preamble; But Constitution Being A Living Document Can Be Amended By Parliament: SC

The Supreme Court has observed that while the Constituent Assembly did not include the words 'socialist' and 'secular' in the Preamble, the Constitution being a living document gives the Parliament the power to amend it in terms of Article 368 of the Constitution.

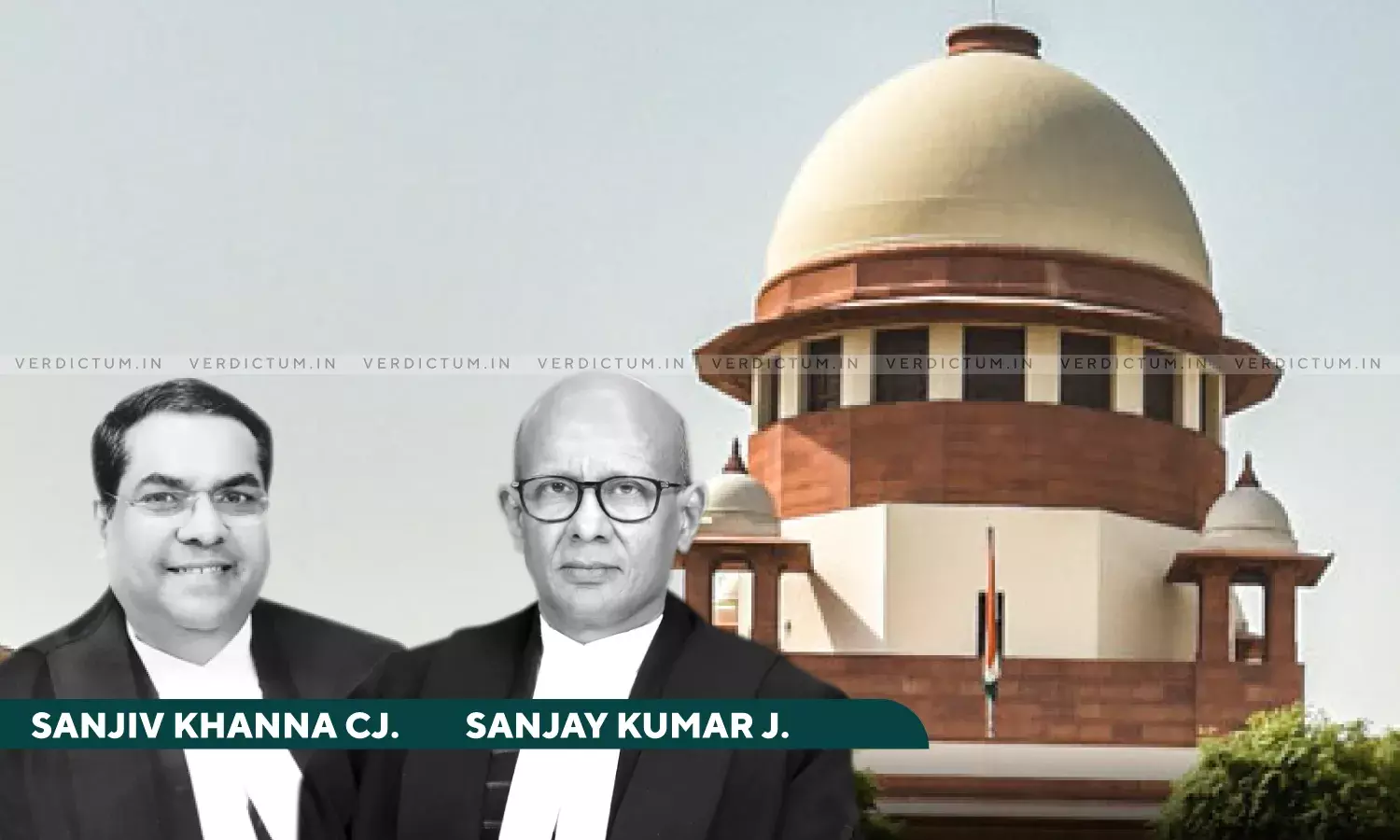

The Court dismissed the Petitions challenging the insertion of the words ‘socialist’ and ‘secular’ into the Preamble to the Constitution. The petitioners argued that the additions, made through the Constitution (Forty-Second Amendment) Act, 1976, were unconstitutional and contrary to the original intent of the Constituent Assembly. The Bench observed that the word ‘socialism’ reflects the goal of economic and social upliftment and does not restrict private entrepreneurship and the right to business and trade, a fundamental right under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution.

The Bench of Chief Justice of India Sanjiv Khanna and Justice Sanjay Kumar held, “While it is true that the Constituent Assembly had not agreed to include the words 'socialist' and 'secular' in the Preamble, the Constitution is a living document, as noticed above with power given to the Parliament to amend it in terms of and in accord with Article 368. In 1949, the term secular' was considered imprecise, as some scholars and jurists had interpreted it as being opposed to religion. Over time, India has developed its own interpretation of secularism, wherein the State neither supports any religion nor penalizes the profession and practice of any faith.”

Senior Advocate G.V. Rao represented the Petitioners, while Advocate Ashwini Kumar Upadhyay appeared for the Respondents.

It was argued that the words ‘socialist’ and ‘secular’ were deliberately excluded by the framers of the Constitution in 1949. They argued that the Forty-Second Amendment Act, passed during the Emergency in November 1976, was enacted by a Parliament that had exceeded its normal tenure. This, the Petitioners claimed, questioned the legitimacy of the amendments, which purportedly lacked the will of the people.

The Supreme Court noted that over time, India developed its own interpretation of secularism, wherein the State neither supported any religion nor penalized the profession and practice of any faith. “This principle is enshrined in Articles 14, 15, and 16 of the Constitution, which prohibit discrimination against citizens on religious grounds while guaranteeing equal protection of laws and equal opportunity in public employment,” it noted.

The Court pointed out, “The Preamble's original tenets—equality of status and opportunity; fraternity, ensuring individual dignity—read alongside justice - social, economic political, and liberty; of thought, expression, belief, faith, and worship, reflect this secular ethos. Article 25 guarantees all persons equal freedom of conscience and the right to freely profess, practice, and propagate religion, subject to public order, morality, health, other fundamental rights, and the State's power to regulate secular activities associated with religious practices.”

The Bench stated that the fact that the Writ Petitions were filed in 2020, forty-four years after the words ‘socialist’ and ‘secular’ became integral to the Preamble, made the prayers “particularly questionable.” “This stems from the fact that these terms have achieved widespread acceptance, with their meanings understood by We, the people of India without any semblance of doubt. The additions to the Preamble have not restricted or impeded legislations or policies pursued by elected governments, provided such actions did not infringe upon fundamental and constitutional rights or the basic structure of the Constitution. Therefore, we do not find any legitimate cause or justification for challenging this constitutional amendment after nearly 44 years,” it remarked.

Consequently, the Court observed, “The circumstances do not warrant this Court’s exercise of discretion to undertake an exhaustive examination, as the constitutional position remains unambiguous, negating the need for a detailed academic pronouncement. This being the clear position, we do not find any justification or need to issue notice in the present writ petitions, and the same are accordingly dismissed.”

Accordingly, the Supreme Court dismissed the Writ Petitions.

Cause Title: Dr Balram Singh & Ors. v. Union of India & Anr. (Neutral Citation: 2024 INSC 893)

Appearance:

Petitioners: Petitioner-in-person Subramanian Swamy; Senior Advocate G.V. Rao; Advocates Ruchi Ranjan Rai, Santi Ranjan Das, Anindo Mukherjee, Vijay Kumar, Rahul Mohod, Sanjay Gyan, Keshav Dev, Mohit Yadav, Aarti Pal, Abid Ali Beeran, Vishnu Shankar, Aditya Santosh, Isha Singh, Anjali Singh, Nalukettil A.S. Nair, Maneesha Sunil, Neha Kumari, S. Anbukrishnan, and Ujjwal Banerjee; AOR Prateek Kumar, Chand Qureshi, Sriram P., Alakh Alok Srivastava and Bijan Kumar Ghosh

Respondents: Advocates Ashwini Kumar Upadhyay, Hari Shankar Jain, Parth Yadav, Mani Munjal and Marbiang Khongwir; AOR Ashwani Kumar Dubey and Vishnu Shankar Jain