SC Proposes Certain Suggestions To Promote Sustainable Conservation Of Sacred Groves & Empower Communities With Their Protection

The Supreme Court has proposed certain suggestions to promote sustainable conservation of sacred groves and empower the communities associated with their protection.

The Court was dealing with an Interlocutory Application concerning the protection of the sacred groves or orans of the Rajasthan.

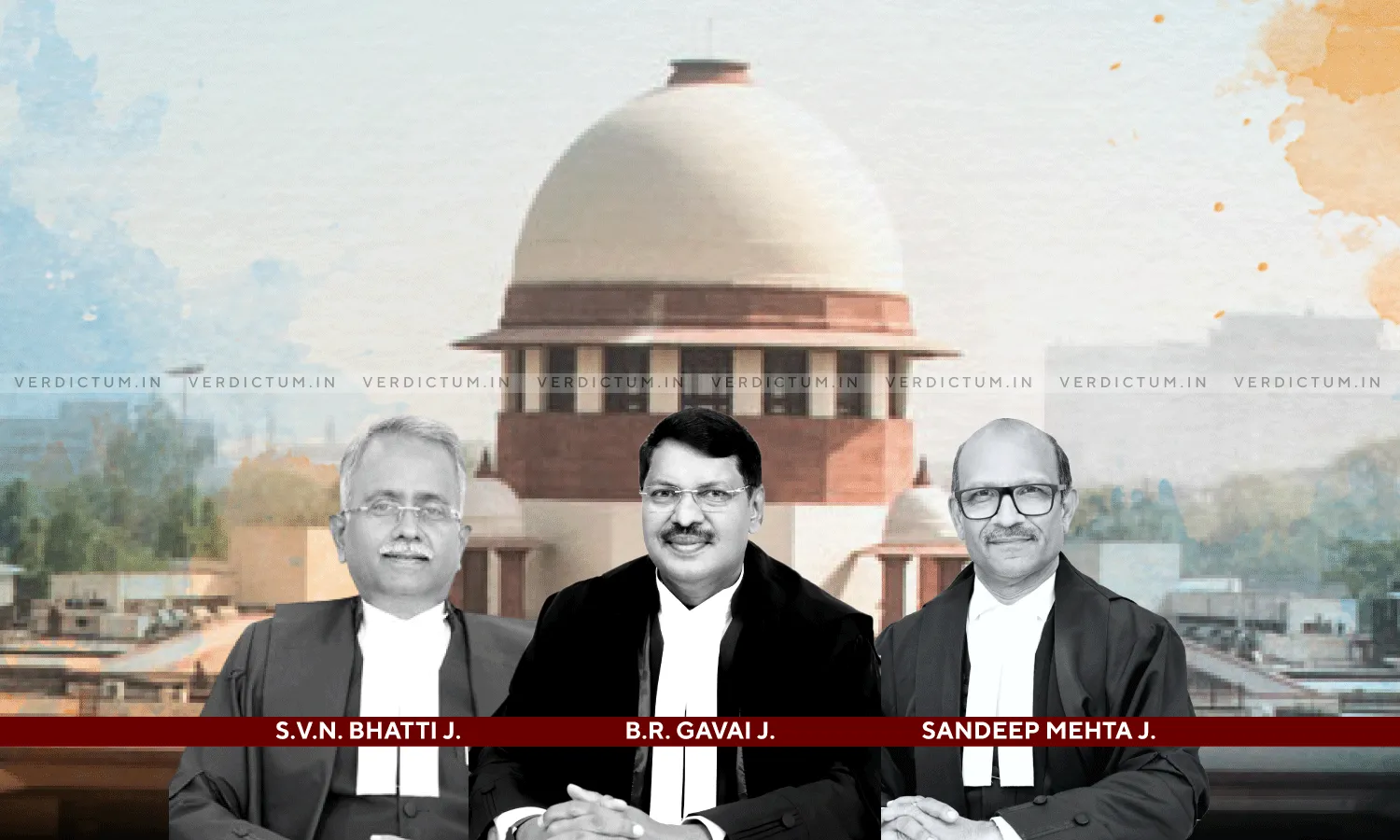

The three-Judge Bench comprising Justice B.R. Gavai, Justice S.V.N. Bhatti, and Justice Sandeep Mehta has suggested the following points –

(i) Section 3(1)(j) of the Forest Rights Act, recognizes the rights of tribal communities under State laws, Autonomous District or Regional Council laws, and their traditional or customary laws. This provision ensures respect for the diverse legal and cultural practices of tribal communities across India. The Rajasthan Government should identify traditional communities that have historically protected sacred groves and designate these areas as ‘Community Forest resource’ under Section 2(a) of the Forest Rights Act. These communities have shown a strong cultural and ecological commitment to conservation, and their role as custodians should be formally recognized. As per Section 5 of the Forest Rights Act, they should also be empowered, along with Gram Sabhas and local institutions, to continue protecting wildlife, biodiversity, and natural resources. Granting them the authority to regulate access and prevent harmful activities would preserve their legacy of stewardship and promote sustainable conservation for future generations.

(ii) Models like Piplantri village demonstrate how community-driven initiatives can effectively address social, economic, and environmental challenges in a cohesive manner. Active measures are required at the Governmental level to ensure that such ideas are implemented/replicated in other parts of the country to promote sustainable development and gender equality. The Central and State Governments should support these models by providing financial assistance, creating enabling policies, and offering technical guidance to communities.

(iii) Sacred groves in different States are managed in various ways. Some are overseen by village panchayats or local bodies created for this purpose, while others rely solely on community traditions without any formal governance. The Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) is recommended to create a comprehensive policy for the governance and management of sacred groves across the country. As part of this policy, the MoEFCC must also develop a plan for a nationwide survey of sacred groves, by whatever name they are identified in each State. This survey should identify their area, location, and extent, and clearly mark their boundaries. These boundaries should remain flexible to accommodate the natural growth and expansion of these forests while ensuring strict protection against any reduction in size due to agricultural activities, human habitation, deforestation, or other causes.

(iv) It must be noted that the National Forest Policy, 1988, carries a statutory flavour as noted in Para 72 of the T.N. Godavarman Thirumulpad(87) v. Union of India19 , Clause 4.3.4.2 of the National Forest Policy, 1988, highlights the importance of encouraging people with customary rights in forests to help protect and improve forest ecosystems, as they depend on these forests for their needs. Therefore, it is suggested that MoEFCC should strive to create policies and programs that protect the rights of these communities and involve them in forest conservation.

Advocate K. Parameshwar was the Amicus Curiae and AAG Shiv Mangal Sharma appeared for the State.

Background -

Sacred groves are conserved by the local residents for a variety of reasons, ranging from belief in a forest deity to the protection of a spring or as sacred space where ancestors are buried. The size of sacred groves ranges from very small plots of less than 1 hectare to larger tracts of land of several hundred hectares. In some cases, these fragments of sacred groves represent the sole remaining natural forests outside of protected areas and, therefore making them some of the last locations with potential for the conservation of flora and fauna. India has the highest concentration of sacred groves in the world (estimated to be over 100,000 sacred groves).

However, these groves are rapidly vanishing due to the increasing demand for timber, urban expansion, deforestation for agriculture, and the pressure to extract natural resources. The sacred groves are known by diverse names across different regions: Devban in Himachal Pradesh, Devarakadu in Karnataka, Kavu in Kerala, Sarna in Madhya Pradesh, Oran in Rajasthan, Devrai in Maharashtra, Umanglai in Manipur, Law Kyntang/Law Lyngdoh in Meghalaya, Devan/Deobhumi in Uttarakhand, Gramthan in West Bengal, and Pavithravana in Andhra Pradesh.

The Supreme Court after hearing the arguments from both sides, observed, “Pursuant to the orders of this Court, the State of Rajasthan has initiated the process of identifying and notifying sacred groves as forests through district-wise notifications. While this development is commendable, it is important to highlight the significant delay in commencing this critical process. Sacred groves of Rajasthan, which hold immense ecological value and are deeply revered in local cultures, urgently require formal recognition and protection to safeguard their preservation. The applicant in the present case has given a list identifying 100 sacred groves in the State of Rajasthan.”

The Court further directed the State of Rajasthan to complete the survey and notification of sacred groves/Orans in all districts and said that the Forest Department must carry out detailed on-ground mapping of the identified groves and classify them as 'forests,' as recommended in the Central Empowered Committee's report.

The Court also referred to Bhagwat Gita Chapter 13 Verse 20 i.e., "Nature is the source of all material things: the maker, the means of making, and the things made. Spirit is the source of all consciousness which feels pleasure and feels pain."

The Court added that, in order to ensure compliance of the directions, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change of India (MoEFCC) in collaboration with the Forest Department, Government of Rajasthan shall constitute a 5- member Committee preferably headed by a retired Judge of the Rajasthan High Court.

“The Committee shall include one Domain Expert, preferably a retired Chief Conservator of Forests, a Senior Officer from the MoEFCC, Government of India and one Senior Officer each from the Forest Department and Revenue Department, Government of Rajasthan. The terms and conditions of the Committee shall be jointly finalized by the Union of India and the State of Rajasthan”, it ordered.

Accordingly, the Apex Court issued necessary directions, disposed of the Interlocutory Application, and listed the matter on January 1, 2025 for receiving the compliance report to a limited extent.

Cause Title- In Re: T.N. Godavarman Thirumulpad v. Union of India & Ors. (Neutral Citation: 2024 INSC 997)