Right To Education Does Not Mean Right To Choose Your School: Apex Court

The Supreme Court today orally remarked that Right to Education does not mean the right to study in a school of one's choice, in a matter where the admission of disadvantaged children in private unaided schools is disputed. The Court was hearing a batch of Special Leave Petitions (SLP), where the lead matter challenges a judgment of the Allahabad High Court which had directed the City Montessori School, Lucknow to admit 13 students in Class-I and Nursery for the academic session 2015-16 adhering to the provisions of the Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Act, 2009) and the U.P. Right of Children to Free and Compulsory Education Rules, 2011.

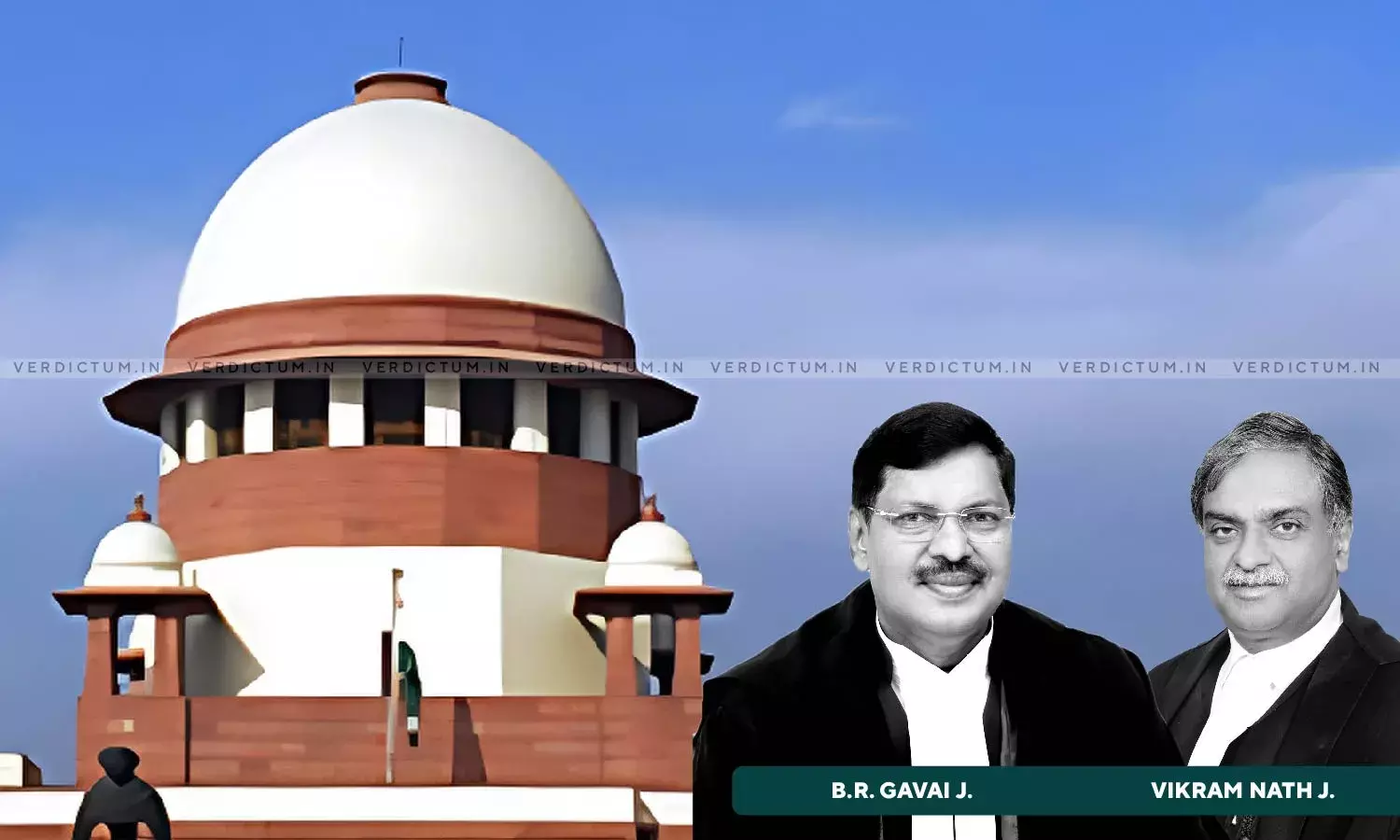

“Why should the State be required to pay the cost when they have facilities available? Right to Education does not mean Right to Education in a school of your choice. You may say that I want my ward to be admitted in a Doon School and the Government should pay for that”, Justice B.R. Gavai remarked during the hearing of the matter. The bench also comprised Justice Vikram Nath.

It is pertinent to note that as per the 2009 Act, Section 12(1)(c) read with Sections 2(n) (iii) and (iv) mandates that every recognised school imparting elementary education, even if it is an unaided school, not receiving any kind of aid or grant to meet its expenses from the appropriate Government or the local authority, is obliged to admit in Class I, to the extent of at least 25% of the strength of that class, children belonging to weaker section and disadvantaged group in the neighbourhood and provide free and compulsory elementary education till its completion. As per the proviso to Section 12(1) (c), if the school is imparting pre-school education, the same regime would apply.

During the hearing today, the counsel appearing on behalf of Education Rights Trust contended that an Amendment to the RTE Act has been made wherein under the Karnataka Rules there is a complete exemption for private schools, that if any government school is there in the neighborhood area then in a private unaided school a disadvantaged child cannot take admission. The same was even upheld by the High Court, which came to be challenged in one of the petitions in the batch of SLPs.

She further submitted that from the last 4 years not even a single disadvantaged child has been given admission in any private school. “While the purpose was to ensure that children from different backgrounds sit together in an inclusive environment, where children from economically backward sections should not be deprived of quality education because they cannot access it”, she added further.

ASG Vikramjit Banerjee appearing for the Union of India said, “we frame the rules, and it is not compulsory that you have to get it, there is flexibility attached to it”.

While counsel appearing for City Montessori School at the outset submitted that if the disadvantaged children are given admission in Private Unaided Schools then the State would have to reimburse the fees under Section 22 of the RTE Act. Therefore, the State would incur double expenditure while Government Schools will lie vacant.

“There is no choice in Section 3 of the RTE Act and in Article 21 of the Constitution of India, that whether a child can opt for a private school and that too to the top most private school when the government schools are lying empty”, he argued.

The Court however was reluctant to accept the arguments that the private schools should extend admissions to the disadvantaged students, when the government schools are lying vacant.

“You are putting the burden on State exchequers because on one hand the State would be having Schools, the students would not be available there and the States would be required to pay the hefty fees of the private schools”, Justice Gavai said.

“State does not have to pay private school fees, State has to pay State’s cost per child”, said the Counsel appearing for the Trust in response.

In the pertinent matter, a writ petition was filed challenging the order passed by the District Basic Education Officer, Lucknow dated April 13, 2015, whereby a direction was given to the appellant-school (CMS) to admit 31 students in Class-I and Nursery as per the provisions of the Act and the Government Orders.

A Single Judge Bench, however, was of the opinion that the arguments of the appellant were not tenable under law and accordingly gave a direction to admit 13 students in the respective classes for the academic session 2015-16 adhering to the provisions of the Act. While the remaining students were to be ensured their admission in any other neighbourhood schools within 15 days, which are recognized and unaided.

In the case, the appellant School had alleged mala fide against the Basic Education Officer and submitted that the Basic Education Officer targeted the school of the appellant with malicious intention. It was contended that as the appellant school has already taken admissions and the seats are full and now it has no seats to accommodate those students.

Further that if admission is allowed as per the order of the Single Judge then it would be difficult for the children to go one kilometer on foot on each side daily as they belong to economically weaker section and can not afford travelling expenses, thereby frustrating the entire purpose of and the very purpose of the Act and the Rules.

However, the division bench, while refusing to accept any of the contentions that the appellant had put forth, observed, "...we find that the arguments of learned counsel for the appellant that admission in respect of neighbourhood, in respect of identification process, in respect of availability of seats and in respect of delayed admission in the sessions, are not substantiated under law. The provisions of the Act as well as the guidelines issued by the Central Government go to indicate that the aforesaid direction given by the learned Single Judge cannot be faulted in any manner".

Cause Title: City Montessori School v. State Of U.P. And Ors.