Due Consideration To Be Provided To Mitigating Factors While Deciding Capital Punishment For Abhorrent Nature Of Crimes: SC

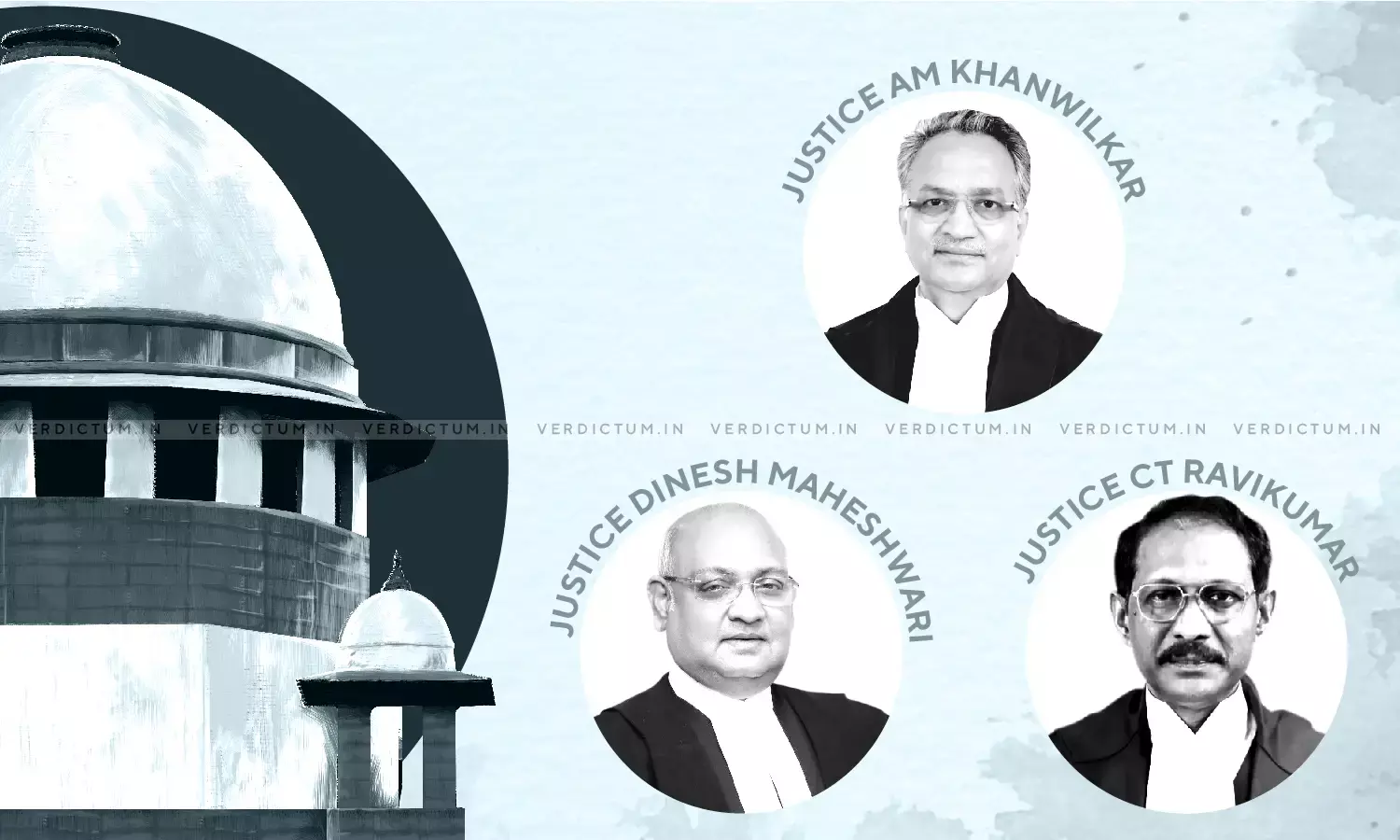

A three-judge bench of the Supreme Court comprising of Justice A.M. Khanwilkar, Justice Dinesh Maheshwari, and Justice C.T. Ravikumar has held that while taking up the question of confirmation of death sentence and making several comments in regard to the abhorrent nature of crime and its repulsive impact on society, due consideration had to be provided to the equally relevant aspect pertaining to mitigating factors before arriving at a conclusion.

In this case, the Appellant had enticed a seven-year-old girl to accompany him on the pretext of picking lychee fruits and thereafter committed rape upon the child which caused her death. He then dumped the dead body near a bridge on the riverbank, after having dragged the dead body over a distance of one and one-quarter kilometers. The accused-Appellant preferred an appeal against the death sentence and the conviction awarded by the Trial Court. The Allahabad High Court dismissed the appeal filed by the Appellant and confirmed the punishment awarded to him, including the sentence of death. The impugned judgment of the Allahabad High Court had been challenged before the Apex Court.

Counsel, Siddharth appeared for the Appellant while Counsel, Anuvrat Sharma, represented the State of Uttar Pradesh before the Supreme Court.

The issues in this case were -

- i) Whether the conviction of the Appellant called for any interference.

- ii) Whether the sentence of death awarded to the Appellant deserved to be maintained or be substituted by any other sentence.

It was contended by the Appellant that there had been inconsistencies as regards the presence of people at the time of lodging the FIR, as regards to the timing of recording the statement of the mother of the victim child under Section 161 CrPC, and also that there had been opaqueness as regards compliance of Section 157 CrPC in dispatching the FIR to the Court.

The Court clearly observed that these factors, whether taken individually or taken collectively, could not be decisive of the questions calling for determination in this case. According to the Court, it was the overall view of the evidence as regards the chain of circumstances that alone was decisive of the matter.

The Court further observed that minor inconsistencies or irregularities could not take away the substance of the matter and the crucial facts proved in evidence. The Court held that a few discrepancies here or there did not establish that the FIR was ante-timed or that the dead body had already been seen by anyone before lodging of FIR. The Court opined that inconsistencies did not take away the substance of the matter where the prosecution had established fundamental facts leading to the chain of circumstances pointing towards the guilt of the Appellant.

The Court further observed, with respect to the first issue-in-hand, "It is hardly a matter of doubt or debate that when 'last seen' evidence is cogent and trustworthy which establishes that the deceased was lastly seen alive in the company of the accused; and is coupled with the evidence of discovery of the dead body of deceased at a far away and lonely place on the information furnished by the accused, the burden is on the accused to explain his whereabouts after he was last seen with the deceased and to show if, and when, the deceased parted with his company as also the reason for his knowledge about the location of the dead body. The appellant has undoubtedly failed to discharge this burden." Thus, the Court held that the Appellant was rightly convicted by the Trial Court and his conviction had rightly been maintained by the High Court.

With respect to the question regarding the correctness of the death sentence awarded to the Appellant, it was opined that while this Court had found it justified to retain capital punishment on the statute to serve as a deterrent as also in due response to the society's call for appropriate punishment in appropriate cases but at the same time, the principles of penology had evolved to balance the other obligations of the society, i.e., of preserving the human life, be it of accused, unless termination thereof was inevitable and was to serve the other societal causes and collective conscience of society.

This had led to the evolution of 'rarest of rare test' and then, its appropriate operation with reference to 'crime test' and 'criminal test'. The delicate balance expected of the judicial process had also led to another mid-way approach, in curtailing the rights of remission or premature release while awarding imprisonment for life, particularly when dealing with crimes of heinous nature like the present one.

In the present case, the impugned orders awarding and confirming death sentence could only be said to be of assumptive conclusions, where it had been assumed that death sentence had to be awarded because of the ghastly crime and its abhorrent nature. According to the Court, it would have been immensely useful and pertinent if the High Court, while taking up the question of confirmation of death sentence and making several comments in regard to the abhorrent nature of crime and its repulsive impact on society, would have also given due consideration to the equally relevant aspect pertaining to mitigating factors before arriving at a conclusion that option of any other punishment than the capital one was foreclosed.

The Court observed, "The heinous nature of crime like that of present one, in brutal rape and murder of a seven-year-old girl child, definitely discloses aggravating circumstances, particularly when the manner of its commission shows depravity and shocks the conscience. But, at the same time, it is noticeable that the appellant has no criminal antecedents, comes from a very poor socio-economic background, has a family comprising of wife, children and aged father, and has unblemished jail conduct. When all these factors are added together and it is also visualised that there is nothing on record to rule out the probability of reformation and rehabilitation of the appellant, in our view, it would be unsafe to treat this case as falling in 'rarest of rare' category."

Hence, the Court, awarded the punishment of imprisonment for life to the Appellant for the offence under Section 302 IPC while providing for actual imprisonment for a minimum period of 30 years.

Thus, the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of the Appellant of offences under Sections 376, 302, 201 IPC and Section 5/6 POCSO. Additionally, the death sentence awarded to the Appellant for the offence under Section 302 IPC was commuted into that of imprisonment for life.

Click here to read/download the Judgment