First Appellate Court Must Consider Evidence On Record, Especially Those Relied Upon By Trial Court - SC

The Supreme Court has reiterated that the First Appellate Court is required to comply with the requirements of Order 41 Rule 31 Code of Civil Procedure (CPC) in its judgment. The Court observed that the first appellate court shall form points of determination and consider the evidence on record in its judgment.

The Bench, in this context, observed -

"From the above settled legal principles on the duty, scope and powers of the First Appellate Court, we are of the firm view and fully convinced that the High Court committed a serious error in neither forming the points for determination nor considering the evidence on record, in particular, which had been relied upon by the Trial Court."

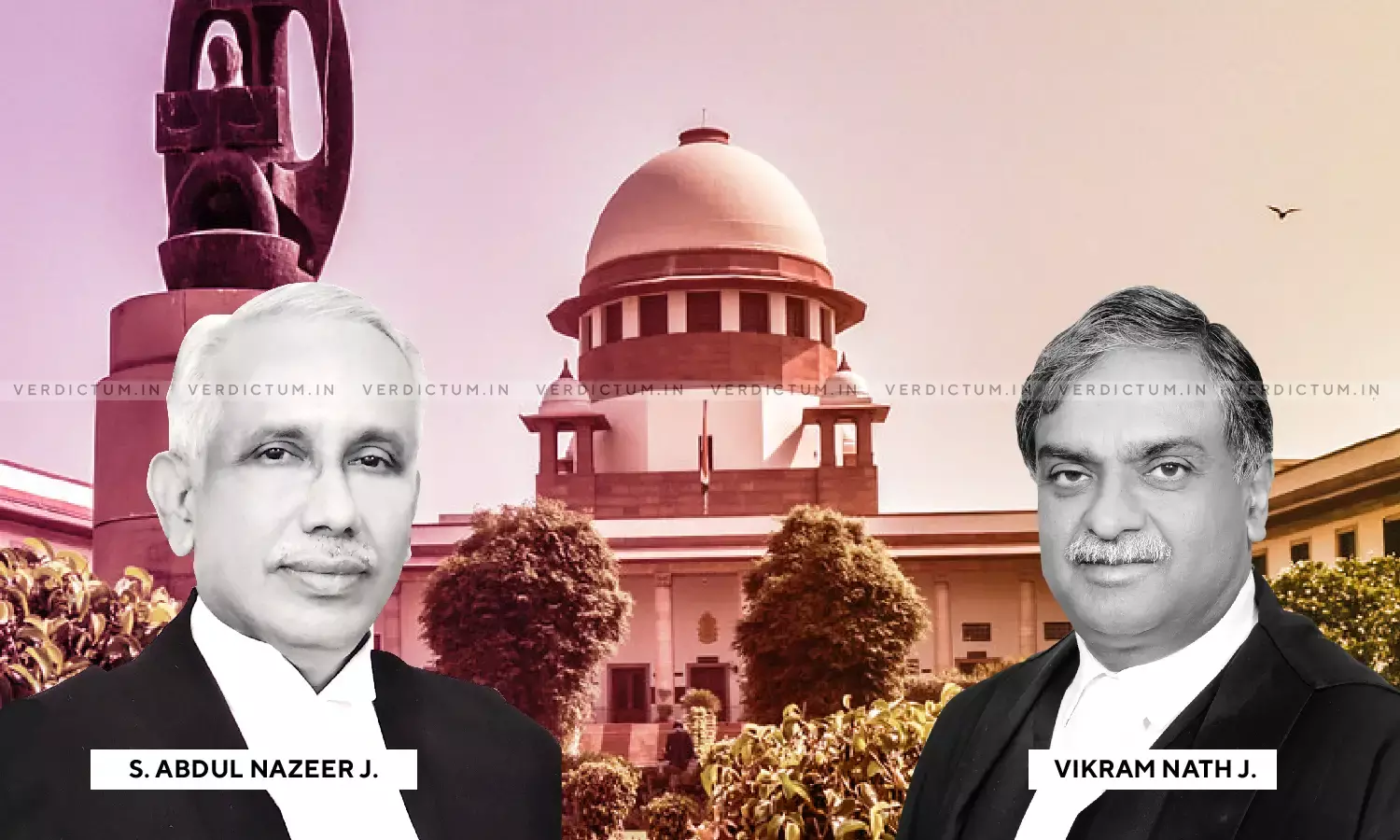

The bench of Justice S. Abdul Nazeer and Justice Vikram Nath was adjudicating upon the scope, power, and duty of the First Appellate Court in deciding an appeal under Section 96 CPC read with Order XLI Rule 31 CPC.

In this case, the appellant's father had ancestral properties and self-acquired properties. The appellant had filed a suit in the trial court where the sole defendant was the brother of the appellant. The appellant had prayed for partition and separate possession of ¼ (one-fourth) share in ancestral properties and ½(one-half) share in the self-acquired property.

The appellant had claimed that she should be entitled to ¼ (one-fourth) share in ancestral properties and further claimed that the property described as self-acquired was exclusively occupied by her father who had applied before the revenue authorities for being declared as an occupant and the same was pending at the time when her father died.

The respondent contested the suit and stated that his father had already spent a substantial amount on the marriage of the appellant and that she was given jewelry worth Rs. 50,000/ and also an additional sum of Rs. 8,000/for establishing a stationarycumcoffee shop. The respondent admitted that the properties were ancestral but stated that the other property was jointly cultivated by him and his father. He claimed that after the death of his father, he was exclusively cultivating the same, and upon the coming of the Mysore (Religious and Charitable) Inams Abolition Act, 1951, he became entitled to occupancy rights and accordingly applied for it, which was granted.

The Trial court decreed the suit declaring that the appellant was entitled to ¼ share in ancestral properties and ½ share in the self-acquired property. Aggrieved by the order of the Trial Court her brother appealed before the High Court.

The High Court upheld the ¼ share of the appellant in the ancestral property but it agreed with the respondent's contention that the alleged self-acquired property was jointly cultivated by the defendant and his father, and that, upon the death of his father, the defendant would get ½ share of his own and the remaining ½ share of his father would be divided between his heirs i.e. ¼ to his daughter and ¼ to his son.

Aggrieved by the order of the High Court, the appellant approached Supreme Court.

The only issue that the Court had to adjudicate was whether the appellant is entitled to ½ share or ¼ share in the self-acquired property over which occupancy rights under the Inam Act were claimed.

The court observed that the during the lifetime of Puttanna, the father of the parties, he was cultivating the self-acquired property on the basis of Panchashala Gutta, and on the coming of the Inam Act, he filed an application for grant of occupancy rights before the Special Deputy Commissioner, Inam Abolition, Bangalore.

The Court noted that the said matter came up before the Land Tribunal, Bangalore and during the pendency of the said application, Puttanna died. Thereafter, the respondent came on record and carried forward the application, filed by Puttanna for occupancy rights, which ultimately came to be granted in his favor.

The Trial Court had noted that occupancy rights were heritable in nature and it is for this reason that after the death of Puttanna, the respondent could get his name substituted and was also successful in obtaining the occupancy rights, but the fact remains that upon the death of Puttanna, the self-acquired property, being heritable in nature, would be inherited by both his children i.e. the appellant and the respondent and under law, both of them would be entitled to ½ (half) share each.

The Court observed that the trial court after perusing evidence on record had ordered that it would be inherited in equal shares by both -the appellant and the respondent.

The Court observed that the High Court in a very cursory and cryptic manner partly allowed the first appeal. The Court noted that "It did not consider the evidence considered by the Trial Court. Neither did it deal with the statements or the other documentary evidence on record and only on a bald statement of the respondent, which according to it, was mentioned in the order of the Land Tribunal that respondent was jointly cultivating the said land along with his father held that it became a joint family estate and, accordingly, reduced the share of the appellant to ¼ (one fourth) from 1/2 (one half)."

The Court observed that the judgment of the Appellate Court should include the points for determination, the decision thereon, the reasons for the decision, and where the decree is reversed or varied, the relief to which the appellant is entitled.

The Court placed reliance on a catena of judgments to deal with the scope, power, and duty of the First Appellate Court in deciding an appeal under Section 96 CPC read with Order XLI Rule 31 CPC.

Based on those judgments the Court held that the High Court committed a serious error in neither forming the points for determination nor considering the evidence on record, in particular which had been relied upon by the Trial Court.

The Court further held that the impugned judgment of the High Court was unsustainable in law and liable to be set aside.

On the question of whether the matter would be required to be remanded to the First Appellate Court, the Court observed "In the facts and circumstances of the present case, we find that the suit was instituted in the year 1991, more than three decades ago; the evidence discussed by the Trial Court is neither disputed nor demolished by the learned Counsel for the respondent. As such, we do not find any good reason to remand the matter to the High Court."

Click here to read/download the Judgment