Refusal To Continue Work Unless Promises Are Performed By Other Party Cannot Be Abandonment Of Contract - SC

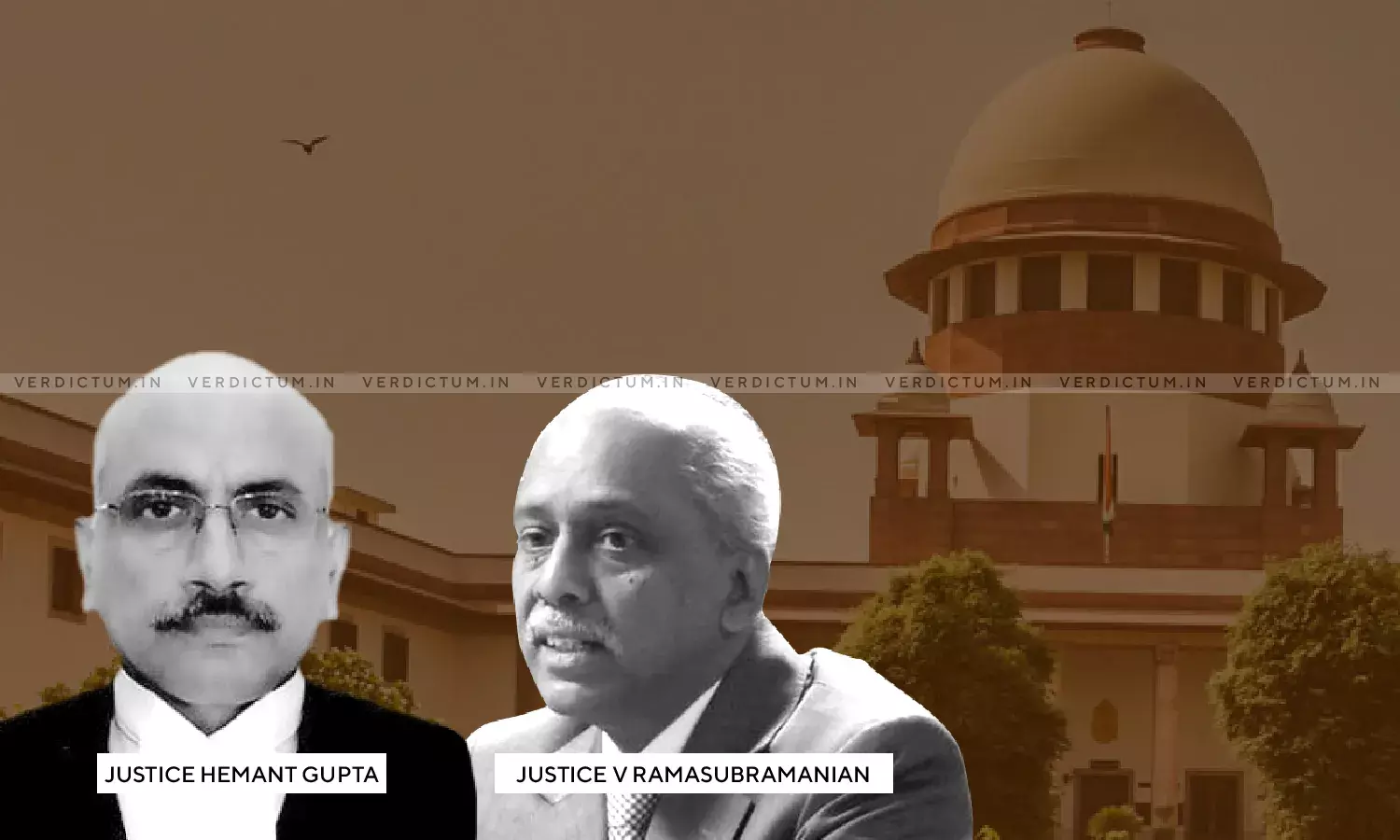

A two-judge bench of Justice Hemant Gupta and Justice V. Ramasubramanian has held that the refusal of a contractor to continue to execute the work, unless the reciprocal promises are performed by the other party, cannot be termed as an abandonment of the contract.

The Court also held that refusal by one party to a contract, may entitle the other party either to sue for breach or to rescind the contract and sue on a quantum meruit for the work already done.

The Court noted, "Section 67 of the Indian Contract Act, 1872 makes it clear that if any promisee neglects or refuses to afford the promisor reasonable facilities for the performance of his promise, the promisor is excused by such neglect or refusal."

In appeal was the judgment of the Bombay High Court rendered in a regular appeal under Section 96 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908 via which the decree of the trial court for recovery of Rs. 24,97,077/- together with interest at 10% p.a. was modified into a decree for recovery of Rs. 7,19,412 together with interest.

Mr.Vinay Navare Senior Counsel appeared for the appellant, and Mr. Sunil Murarka Counsel appeared for the respondents.

The appellant being a registered contractor with the Government of Maharashtra was awarded a successful tender for the execution of the work of the Regional Rural Piped Water Supply Scheme for Dabhol Bhopan and other villages in Ratnagiri District.

The appellant issued a work order for a cost that was above 47% of the estimated cost. The R-3 issued a letter informing the appellant that the work order was kept in abeyance. After a few representations, R-3 informed the appellant to start the work.

Later, he was informed about the non-availability of C-1 pipes and cement pipes. The respondents desired a change in terms of the work order and hence appellant demanded a modified rate.

In the interregnum, R-3 instructed the appellant to stop the pipeline work and start the work of construction of another work at a different place. The bills raised by him were not honored and hence appellant did not proceed with the work.

Appellant then filed a suit for recovery. The trial court decreed the suit partially. The respondents preferred a regular appeal with the Bombay High Court. The appellant did not file any appeal. The High Court partially allowed the appeal.

Hence, the instant appeal.

The Supreme Court noted the controversy in brief as follows:

"As could be seen from the above table, what was allowed by the Trial Court under three heads of claims namely, (i) the release of security deposit to the tune of Rs.2,21,000; (ii) overheads for the period from January 1989 to 30.09.1990 to the tune of Rs. 5,63,115/; and (iii) loss of profits to the tune of Rs.9,73,250/, were disallowed by the High Court. Therefore, the appeal before us is actually confined only to these 3 heads of claims."

The Court, after noting the timeline of events that transpired, held that the appellant was not guilty of anything including abandonment. The Court noted that Clause 3(a) of the contract enabled respondent to rescind the contract and forfeit security as also entrust work to another contractor. The Court noted that this clause was not invoked.

On the issue concerning abandonment, the Court made the following crucial observations:

"It is fundamental to the Law of Contract that whenever a material alteration takes place in the terms of the original contract, on account of any act of omission or commission on the part of one of the parties to the contract, it is open to the other party not to perform the original contract. This will not amount to abandonment. Moreover, abandonment is normally understood, in the context of a right and not in the context of a liability or obligation. A party to a contract may abandon his rights under the contract leading to a plea of waiver by the other party, but there is no question of abandoning an obligation. In this case, the appellant refused to perform his obligations under the workorder, for reasons stated by him. This refusal to perform the obligations, can perhaps be termed as breach of contract and not abandonment."

The Court held that the finding of the High Court that there was an abandonment of contract was completely contrary to another finding that the period of contract was till June 1989 and that respondents themselves granted an extension of time to complete the contract up to 31.12.1989, despite there being no request from the appellant.

Hence, the Court held that High Court was in error in overturning the judgment of the Trial Court. The appeal was allowed, and the judgment of the High Court was set aside.

Click here to read/download the Judgment